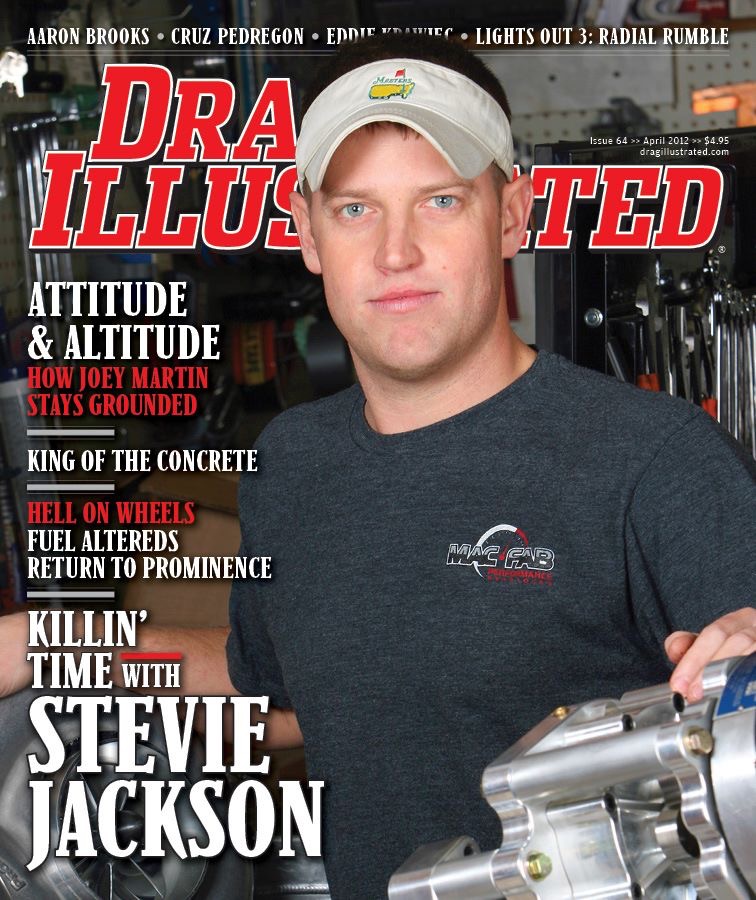

Has any drag racer in the history of the sport wanted it as bad as Stevie Jackson? Look at him now, leaning up against the quarter panel of the bright orange Ford Mustang he made his name with, blue jeans, six-year-old Redback work boots, a Matco Tools uniform shirt, bright blue eyes, wide smile, brownish-blonde hair sticking up out of his patented sweat-stained visor and aura of infinite self-confidence.

[Editor’s Note: This story originally appeared in DI #64 in April of 2012.]

He is talking about something or other—maybe an upcoming race (“I’m going down there to crush people’s souls; we’ll put every one of ‘em on the trailer.”), maybe the shock settings he’ll try on the first pass, maybe the race amongst he and a small group of his drag radial peers to be the first to break into the 4.20s (“We got to do it first. If we don’t I’ll have to listen to it all year or have to run a teen to shut ‘em up”).

In truth, however, it’s hard to hear anything over the blaring insanity of this guy’s dedication and passion for drag racing. This shop, for instance, wouldn’t exactly fit in on Nitro Alley in Brownsburg, Indiana; it’s nice, clean, 900-square-feet, and packed with every imaginable tool, but there’s no on-site machine shop, no front office or showroom, nor army of hired help.

Then there’s the Fox-body Mustang that sits inside the two-car garage, which is responsible for innumerable victories on the drag strip – from grudge races to big money drag radial races to an Outlaw Racing Street Car Association [ORSCA] championship—including eight wins in 12 final-round appearances last season alone (“The only thing we did more of than winning last year was listen to people cry”). And then there are the records, always bordering on unbelievable, always a mile ahead of the competition, and when they happen, it’s almost always with little fanfare or mainstream appreciation. Really, it’s almost unbelievable and nearly too much.

And so here he stands, still running wide-open after a 12-hour workday, saying, “I think one of the major misconceptions about me is that I have money or that I came from money. They see me at the track and we’ve got really nice stuff—it’s old, but we take care of it—and they think that I’ve got deep pockets or something. What they don’t understand is that 90 percent of my worldly possessions are right there with me at the track. I live in a small house, in a small neighborhood; most every dollar I’ve ever made I’ve spent on race car stuff. I’m a working-class guy.”

And so here he stands, still running wide-open after a 12-hour workday, saying, “I think one of the major misconceptions about me is that I have money or that I came from money. They see me at the track and we’ve got really nice stuff—it’s old, but we take care of it—and they think that I’ve got deep pockets or something. What they don’t understand is that 90 percent of my worldly possessions are right there with me at the track. I live in a small house, in a small neighborhood; most every dollar I’ve ever made I’ve spent on race car stuff. I’m a working-class guy.”

Case in point, how today unfolded: “Let’s see,” he says. “I got up at 6:00 to my dog, Dyno, barking at me. He’s a Boston Terrier. His full name is Chassis Dynamometer Jackson and he’s nine-years old. Anyway, I was on my route by 7:00, worked through lunch—ate a sandwich in the truck—and got back home around 6:00. Covered about 200 miles, 32 shops, and spent the next couple hours doing inventory and then headed out here to the shop to work on the race car.”

Seriously? How could it even be possible? The early mornings, the late nights, the cross-country treks, the dog named after a horsepower-measuring device, the dollars spent; you name it, he’s done it, and all in the name of drag racing. What about life away from the drag strip, things other than going fast? Yeah, he doesn’t know, either.

All the time he has somebody talking about him—good, bad, ugly, really ugly—and it almost always harkens back to how well his car performs, specifically how much better it performs than that of those doing the talking. He’s got the baddest drag radial-equipped race car on the planet. He’s one of the few racers that could claim he wins more than he loses. He’s among the very few that can trump the investment of cubic dollars into a race program with ingenuity, hard work and natural ability. Furthermore, he’s known in the grudge racing circles as the king of trash talk and in organized racing series as a frontrunner and trendsetter. To the left, he’s kind of a professional racer; to the right, he’s more like a rebel without a cause. He’s certainly a guy you can count on.

“One thing about Stevie,” says Phil Shuler, who helps tune his car, “is that he is hands-down the most determined, do-anything-to-win racer that I’ve ever been around. He wants to compete against the best there is, and he’s not afraid of anybody.”

So, he’s got the sickness. His entire life revolves around drag racing. And you can ask anyone—he’s always like this. The Stevie Jackson you see at Carolina Dragway on Grudge Night is the same Stevie Jackson you’ll see racing for $20,000 at an organized event, is the same Stevie Jackson who drives a Matco Tools Truck through the week, is the same Stevie Jackson who is sitting here right now saying, “All I’ve ever wanted to do was drag race.” And he means it.

Want to know how exactly this addiction came to be? Thrusting his head forward, he’s more than proud to answer that question. “When I grew up, my dad raced,” he says. “I never wanted to be a fireman or a president or any of that; I wanted to drive a race car. You see the movie Talladega Nights and you laugh at the little kid, Ricky Bobby, but that’s me. My dad started hauling me around to the track with him when I was 6 or 7 and it’s been downhill ever since.”

Want to know how exactly this addiction came to be? Thrusting his head forward, he’s more than proud to answer that question. “When I grew up, my dad raced,” he says. “I never wanted to be a fireman or a president or any of that; I wanted to drive a race car. You see the movie Talladega Nights and you laugh at the little kid, Ricky Bobby, but that’s me. My dad started hauling me around to the track with him when I was 6 or 7 and it’s been downhill ever since.”

And Jackson, now 31, has never wavered; living every day by the motto scrawled across a Winston banner he pulled off a fence after the first NHRA event he ever attended that reads, “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Drag Racing.”

At the same time, however, that doesn’t mean all he’s ever done is load up his race car and head to the track. He’s well aware of the fact that this hobby-turned-part-time-career of his is something that only a small percentage of the population of the planet are given the opportunity to do as their full-time employment. To be a professional drag racer in this modern era it takes elite-level wealth or major-league connections—generally a combination of the two. Jackson has neither, but it’s not going to stop him from trying.

“The theory is basically if I keep winning and outrun enough people with money, they’re eventually going to get tired of me whooping their ass and hire me.” It’s not a bad approach. And it works well for someone who gets such immense satisfaction from doing more with less; even though he readily admits he’s nowhere near the underdog he once was when he first rolled out a ProCharger-equipped, conventional-headed, less-than-trick, big-block-Chevy-powered Mustang amongst a field of dominant twin-turbocharged cars.

“There are guys that I race against that have three and four times as much invested as I do,” he says. “There are guys out here spending $400,000 a year. And there’s a lot of guys just like me, and a lot of guys that have less than I do. But a majority of the cars I race against are owned by people who could afford to run Pro Mod if they wanted to. They just want to sit down and run against slower cars. I’m whooping their ass, though, and there’s nothing I love more. I love to pick on rich people.”

One day when Jackson was 13 years old, he stole his mother’s car and drove it straight to the drag strip, lied about his age, and entered the trophy class. From the time he could comprehend the power and freedom provided by a driver’s license, he counted down the days till his 16th birthday. His father had been down this road, though, and wasn’t thrilled that his son wanted to follow in his footsteps.

“My dad was completely against me racing; he knew how much it cost, so he knew it was a bad idea. Still, he helped me get a Camaro when I turned 16, but it was a V6. He made sure I had the slowest car on the planet. I started racing it, put nitrous on it, ripped the seats out of it— being a dumb kid—just doing anything to make it run better. Back in ’96, it ran 18s and I thought I was the shit. Pretty soon I realized how slow it was and got rid of it.”

Around that time, Jackson, who admittedly comes from rather humble beginnings, realized the only way he’d ever have something fast was to work for it. He’d make mention of something he wanted or wished he had and his mother would tell him to get a job. So, that’s exactly what he did—two of them, in fact. Working two full-time jobs, Jackson still managed to graduate high school, and when he did—unlike his friends whose parents booked them trips and bought them cars—he got a carburetor, a 750cfm Holley double-pumper, and it was all he wanted. “Kids today have so much handed to them and feel so entitled. I’m a firm believer that if you want something, you need to work for it. Otherwise you’ll never truly appreciate it.”

Having unloaded his embarrassingly slow Camaro, Jackson picked up a rough-around-the-edges Chevy S10 pickup, and promptly stuffed a 327 ci small-block Chevy between the frame rails (“This thing was the biggest piece of shit”). Two shades of blue and nitrous-injected, Jackson’s little truck would make the trek to the track and then be transformed into race-mode. He’d yank out the seat, put in a little plastic one, unbolt the exhaust, change the tires, and proceed to tear it up bad enough that it wouldn’t pull itself home. More often than not he’d wind up working all night at the track to get it running again just so he could drive home and be ready for work in the morning.

Wrenching on cars had basically become second nature and within a few years had actually become Jackson’s profession. “When I grew up, if you were a mechanic and raced cars, that was cool,” he says. “Honestly, working as a mechanic was all I could do; I didn’t know anything else. I went and got my master technician certifications for Ford and GM and started working at a dealership.”

On the drag strip, he continued to progress as well. The S10 became an increasingly serious race car—new paint, bigger, fancier engine, roll cage. And it got fast. With a bottle-fed big block under the hood, it would run 5.20s on any given race day. By 2005, Jackson couldn’t resist the urge to try and compete in an actual series, but faced the harsh realization that he simply couldn’t afford to do it. When his local tool dealer stopped by the dealership one afternoon and told him he should put his colorful and lovable personality and natural gift of gab to work in the tool business—as well as revealed the potential earnings of doing so—Jackson decided to take the leap of faith.

“I realized I could make more money selling tools and I knew if I had more money I could race more. The fact that I could set my own schedule didn’t hurt, either. I didn’t know anything about the tool business, but he showed me the opportunities, and I knew it was what I had to do. It was a big step towards being able to buy better parts and do more racing.”

Jackson dived in head-first, made the required investment to become a Matco Tools Franchisee, leveraged his work ethic and horse trader skills, and started racking up miles on his route in and around Augusta, Georgia, the town where he was born and raised. As with any entrepreneurial endeavor, the early goings did little to afford him additional time or money to go drag racing, but the potential was obvious from the onset. The business began to grow; Jackson started making himself a modest living, and as soon as he could justify it started to invest more of his time and earnings into his race program.

Jackson dived in head-first, made the required investment to become a Matco Tools Franchisee, leveraged his work ethic and horse trader skills, and started racking up miles on his route in and around Augusta, Georgia, the town where he was born and raised. As with any entrepreneurial endeavor, the early goings did little to afford him additional time or money to go drag racing, but the potential was obvious from the onset. The business began to grow; Jackson started making himself a modest living, and as soon as he could justify it started to invest more of his time and earnings into his race program.

Again, the most important thing to know about Jackson’s past is that every move he’s made since the beginning has been made to better position him to drag race full-time; nothing more, nothing less.

“It started out as an all-day, almost every day deal,” he admits. “But as the racing got bigger, it kind of encroached on the business, and now racing is a part of my income. We race a lot and do fairly well, so I’m able to run the tool franchise three days a week. It’s three days from six-to-nine; three pretty long days. There’s not ever a day off, but I’ve got my route to where I can do it and have Fridays to get the car ready to race and Mondays to fix whatever we tore up. My manager hates it, but he can’t do anything about it.”

With the Outlaw Racing Street Car Association in its prime in early 2008, Jackson, who had now acquired his soon-to-be legendary, notch-back Mustang, made his extremely loud and rambunctious debut in the series’ radial-tire category, E/Z Street. By the third round of qualifying at the first event he had ever attended he had already blasted the standing E.T. record and when the smoke cleared after a tire-smoking, pedal-thumping final round, left with the winner’s check and trophy. Between the mere sound of his Mustang’s ProCharged engine combination (“She sounds like a herd of ticked-off Tweety birds”), Jackson’s in-your-face personality, and the numbers posted on the scoreboard by the two, there wasn’t a radial tire racer in the country who wasn’t immediately aware of them. It wasn’t all winner’s circle photos and white time slips, but the year ultimately ended with Jackson’s first-ever series championship and the full-attention of the outlaw racing world.

As insatiable as he is determined, Jackson moved up to Limited Street the next year to face stiffer competition, but remained on the D.O.T.-approved radials and stock suspension setup he’d seen such success with despite the class rules allowing him to run ladder bars or a four-link, as well as 29×10.5-inch slicks. Jackson and the “orange car,” as he often refers to it, continued on their tear, setting and resetting his own record on two occasions and locking up a second-place finish in the points for a rain-hampered season that dwindled down to just five races from ten.

Continuing his trend of constant advancement, he briefly teamed up with another racer to embark on a campaign in Outlaw 10.5, but after grenading the engine the second weekend out, they had to shelve the project. In the fall of 2010, nearly a year since he’d last raced on radials, Jackson showed up for the Outlaw Radial Tire Championships Radials vs. The World event in Valdosta, Georgia, to prove to the masses that he hadn’t lost a step.

Of course, he had not.

Dyno rubs up against his leg and whimpers. Jackson pets his head. Though not inseparable, he and this little terrier spend “a good bit” of time together. With his business and his racing, there’s hardly time for companionship or anything else that requires much more effort than a dog does. “I don’t know any person that loves racing and the competition more than me. Competition is all that drives me. I want to be better than anybody else out there. It’s not that I’m arrogant or an asshole, but the fact is when I’m sitting there by you on the starting line, I believe in my mind I’m better than you and I want to crush you. As soon as I outrun you, we’ll be best friends again. ‘Till then, I want to crush you.”

Where does this fire in his belly come from? He says, “I guess it’s because I grew up poor. I don’t feel like any man is better than me. My stepfather raised me, and he always told me never ever be afraid to be a better man. Never be afraid to be better at life. Never be afraid to be better at drag racing. He’d say that no matter what you do—life, racing, work—somebody always has to lose. There’s always competition. I don’t want to be that guy. I hate losing way more than I like winning.”

But that doesn’t mean he doesn’t really enjoy winning. There are those that compete and play it safe; do everything they can to avoid losing. There are also those that compete and swing for the fences; do everything in their power to ensure victory. Stevie Jackson races to win.

“Personally, what’s so awesome about this outlaw radial deal is that it’s a group of guys that are fierce competitors. They want to crush me just as bad as I want to crush them, and I love it. The more the merrier. They think like I do; that if you race against faster cars you become a better racer. It’s like a royal rumble out there.

“Kevin Fiscus and I have been going back and forth with the record for four years now. He’s had it several times; I’ve had it several times. There are five or six cars that can go out there and run as fast as we can at any given time; it’s dog eat dog. But the awesome thing is that every one of those guys is like a brother. If I needed a part, they’d overnight it to me. Not everybody likes me, but we get along well with most everybody. Some people don’t like me because I don’t split purses. Look, I don’t just want to run—I want to run for first and second.”

He’s incredibly serious about racing, but it’s not fueled entirely by passion. A good bit of his intensity has to be attributed to his grudge-racing days on the meanest strips in the South against some of the roughest, rowdiest, and fastest crowds there are. On that side of the fence, where the stakes are high and mistakes are permanent, it’s hard not to develop a complex that every race is do-or-die.

“I have to attribute everything I am as far as my personality and for us having as much success as we have to grudge racing. In grudge racing, you’ve got one pass; every time you run it’s the final round. That’s the first kind of racing I ever did, and it wasn’t because we wanted to race for money, it’s because we couldn’t afford to build cars that would pass tech and be legal for a sanctioned event. I’m not going to lie, most grudge racers would love to be out class racing somewhere, but it’s a lot of hassle, a lot more money, and I’ve got to admit there’s a big attraction to sitting on the starting line and racing one time for $20,000.”

“I have to attribute everything I am as far as my personality and for us having as much success as we have to grudge racing. In grudge racing, you’ve got one pass; every time you run it’s the final round. That’s the first kind of racing I ever did, and it wasn’t because we wanted to race for money, it’s because we couldn’t afford to build cars that would pass tech and be legal for a sanctioned event. I’m not going to lie, most grudge racers would love to be out class racing somewhere, but it’s a lot of hassle, a lot more money, and I’ve got to admit there’s a big attraction to sitting on the starting line and racing one time for $20,000.”

Jackson also recognizes that the situations he faced in the grudge racing circles have a direct correlation to the way he runs his race program—detail-oriented, strategic and analytic.

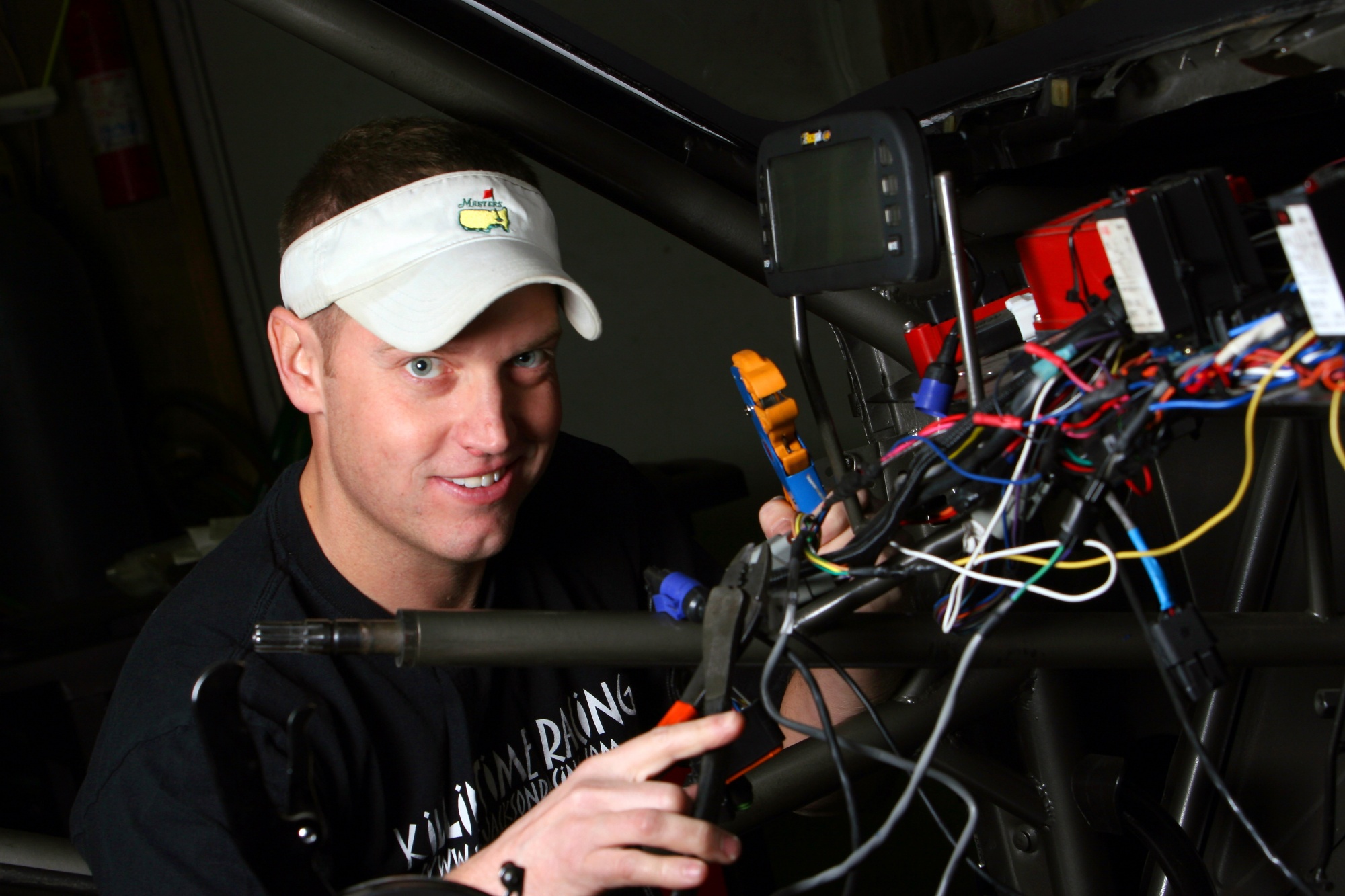

“I’ve raced for enough money to pay off most people’s houses and when you’re bumping into that second beam dealing with that kind of pressure, you can’t be worried about the car. One little thing goes wrong and it costs you—a lot. Having started out like that, I probably maintain my car and check everything more than anybody at the track. There’s times when we take the heads off between rounds; we just want to check the gaskets, make sure everything is perfect. The more you check; the more problems you’ll catch.”

Having been away from the scene for a little bit, he misses the thrill, but word travels fast in the racing community and it doesn’t take long before getting a race is next to impossible. What he misses most, though, is the trash talk. “I’m really good at it. I’ll stand there toe-to-toe with somebody two-feet taller than me and talk about their mom. People love to watch that. I got respect because if I told you I was going to kick your ass on the track, most of the time I kicked your ass. I’m not a big guy, I’m no brawler, but I’m not backing down from anybody or anything.”

It’s true, too, but that’s not to say he’s fearless. Let’s say he’s thinking about approaching a company about a sponsorship, or pitching a deal to a manufacturer. He instantly clams up. He gets uncomfortable. And when the time finally comes, he quickly convinces himself that he’ll be fine without. “I’m terrible at asking for help. When I go out and I meet these sponsors, I feel like I’ve got my hand out. It’s kind of funny; you look at me at the track and you can tell I love talking to people, but I’m terrible at marketing; I’m not good at asking people for stuff. I’ve got too much pride.”

Jackson is sufficiently self-aware to grasp what sets him apart. Unlike some racers who might have better equipment or deeper pockets, he recognizes there is no replacement for hard work. “I say to all my guys that elapsed time is directly related to the amount of work you put into it. The harder you work; the lower that number gets. Not everyone wants to hear it, but that’s the truth. You can’t take a break and expect to run fast.”

In 2007, he made friends with a fellow grudge racer, who appreciated Jackson’s work ethic and ability behind the wheel and asked him to drive his car. That individual was Shuler, a fellow Southerner, who makes his living as an NHRA Top Fuel crew chief under the Don Schumacher Racing umbrella. The two clicked immediately and it wasn’t long before Jackson was tagging along with Shuler to the races and vice versa.

“Going to the races with Phil and hanging around with a Top Fuel team has benefitted me knowledge-wise more than anything,” he says. “You spend much time around these guys that race for a living and you realize that every detail, even the itty-bitty ones, makes a difference in how your race car performs.”

Shuler’s professional approach and near-infinite mechanical expertise rubbed off on Jackson immediately, and it was intriguing to the top-level nitro tuner how similar Jackson’s drag-radial Mustang was to a Top Fuel dragster. “We talked about it several times early on; how they’re extremely close, a fuel car and a radial car, as far as the horsepower-to-tire ratio. Both are extremely sensitive and both have more power than they can ever use.”

Having the opportunity to drive for Shuler, all the while fielding his own team, exposed him to a variety of different things and thought processes that he could then apply to his own car. “Basically, I started to look at how Phil tuned his car versus how I tuned mine and I was like, ‘Man, he looks at all this little stuff.’ And at that time we didn’t even have a RacePak. I didn’t even know what a RacePak was. The more time we spent together, the closer we got, and by 2009 we were like best friends. We talk every day.”

Jackson knows he isn’t the only racer in drag radial that’s working hard at running well, but he knows that isn’t all it takes. “Everyone thinks there’s one special reason we run fast, one special part or one-off piece, but it’s not. It’s a million little things. Have you ever heard Al Pacino’s speech from Any Given Sunday? ‘On this team, we fight for that inch. On this team, we tear ourselves and everyone around us to pieces for that inch. We claw with our fingernails for that inch. Cause we know when we add up all those inches that’s going to make the difference between winning and losing, between living and dying.’ It might sound a little extreme, but that’s my motto; that’s how our little team approaches racing.”

Everyday when he wakes up, despite his acknowledgement that this is a game won and lost by tiny increments, he thinks about how completely out of control drag radial racing has become and how quickly it happened. “It took 10 years for someone to go 4.70s on radials and three years to get into the 4.30s,” he says. “It happens pretty fast. And as long as there is no limit on horsepower, I don’t see us slowing down anytime soon.”

Much like in fuel racing, going fast on drag radials is all about power management, something Jackson is known for being “pretty good at.” The radial tire functions dramatically different than the standard slick tire used in drag racing, making it a tightrope walk for Jackson on virtually every eighth-mile attempt that could result in a world record, tire smoke—or back flip.

“The thing about a radial versus a slick is that a radial tire can’t spin at all ever during a run,” he explains. “It has to be glued to the track. If you look at the driveshaft curve on a radial tire car, it’s straight from A to B. The faster you go, the taller the line gets. So the limit of the tire, the lowest possible E.T. is going to be related to how many times that tire can roll over in the eighth-of-a-mile without coming unglued. So, at some point you’re going to have to see advancements in traction compounds, it’s going to get temperature related and weight sensitive front-to-back. There will be a stopping point—it’s just coefficient of friction. At some point there will be a limit to how many rotations that tire can make in 660-feet without coming unglued. I don’t know what that number is.”

“The thing about a radial versus a slick is that a radial tire can’t spin at all ever during a run,” he explains. “It has to be glued to the track. If you look at the driveshaft curve on a radial tire car, it’s straight from A to B. The faster you go, the taller the line gets. So the limit of the tire, the lowest possible E.T. is going to be related to how many times that tire can roll over in the eighth-of-a-mile without coming unglued. So, at some point you’re going to have to see advancements in traction compounds, it’s going to get temperature related and weight sensitive front-to-back. There will be a stopping point—it’s just coefficient of friction. At some point there will be a limit to how many rotations that tire can make in 660-feet without coming unglued. I don’t know what that number is.”

Jackson is confident the tire developed by Mickey Thompson will support a run in the mid four-teens over the eighth-of-a-mile at weight and without wheelie bars. Which, unfortunately, begs the question of whether or not these cars that generally weigh well over 3,000-pounds have far surpassed even a loose definition of safe. It’s something he thinks about almost every day when he wakes up, but it’s really not the speeds his and other cars are moving these days that concern him.

“When you start getting into the low fours, it takes a driver who is aware of how fast that is,” he says. “I worry about it. It’s the same thing in Pro Mod. The reason you see more wrecks now than you used to is because people can afford to buy cars that are beyond their ability to drive. I started out running 18 seconds and I’ve made a million passes. A lot of people don’t have that built-in switch that tells them when to step off the throttle. These cars all recover very fast if you know when to say when.”

He’s had his spills and thrills, but he’s adamant that almost every on-track accident is avoidable if the driver realizes his or her responsibility. “I’ve wrecked. I’ve pushed the car too far. You see it time and time again; you’re out there, your adrenaline is pumped up, you’re excited, the thing shakes the tires, you stand back in it, and pile it straight into the wall. I like to think of myself as a conservative driver in qualifying and testing. In eliminations, I’ll admit I’m an extremely aggressive driver. But I always think of the person in the other lane’s safety above my own. The last thing I want is to have somebody ram into me, and that’s the last thing I want to do to anybody else.”

At one point in time, the drag radial pits at any given heads up event were out on the back 40, providing racers with ample dirty, rutted-up, grass pit space to prepare to race for less money than they spent traveling to the event. The class generally served as filler for races that featured headlining classes like Outlaw 10.5 and Pro Modified on the marquee.

“Up until a couple of years ago, we radial guys were at the bottom. Then people like Donald Long started putting on these big-money races and kind of brought what we do into the national spotlight. I still don’t think we get our due, but it’s a lot better now than it was. Radial racing is exciting; you never know what’s going to happen and for the most part all these cars look like something you could drive on the street.”

In the corner of Jackson’s modest race shop is a refrigerator. Not much different than what you’d find in any number of drag racers’ garages; covered in decals, loaded with ice cold refreshments. On the door a big picture of a black-and-blue, late-model Ford Mustang is taped up at eye-level. This isn’t a car he’s ever owned or driven: it’s the car piloted by Kevin Fiscus, the gentleman who snatched away Jackson’s E.T. record during a recently rained-out event at South Georgia Motorsports Park by one-thousandth-of-a-second.

“The guys make fun of me, but anytime somebody outruns me, their picture goes up on the fridge and it stays there until I crush them,” Jackson says. “Fiscus is back on the fridge. He was on the fridge for a while, then we took him off there and nobody was on the fridge. Well, he’s back. That’s every fridge, too; the one in the shop, in the house, and the motorhome.”

Jackson has done everything imaginable to advance his racing career; license in a Top Alcohol Dragster at Frank Hawley’s Drag Racing School, hire an agent, but none of it’s worked. “I want to race the fastest cars on the planet,” he says. “And the fastest cars on the planet are nitro cars. The radial class is something I can barely afford, but it’s something I can kind of afford. I’d jump out of it in a heartbeat to drive a Pro Mod or nitro car. It’s nice being a big fish in a small pond, but I wouldn’t mind it being the other way around.”

For the time being, Jackson is more than content scrapping with the best small-tire racers he can find. “It’s not like this deal is easy and I’m looking for a bigger challenge; I’d just like to go faster. These cars are as challenging as any. Like I said, it’s a million small things. Every run, we adjust everything from the shocks to launch RPM to timing graphs to fuel flow and boost. I don’t use any optical sensors, and I don’t use traction control or wheelie meters or any of that stuff. I can’t have traction control or something trying to slow my car down. Power management is our biggest thing. It’s the least understood and it’s the most critical part of these cars. If I’m a tenth of a degree off on my timing graph, this thing won’t go down the track.”

It’s no surprise that the 3,000-plus horsepower produced by the “sporty” and “specific,” yet undisclosed displacement big-block that’s force fed 50 pounds of boost by a new gear-driven F3R-136 ProCharger beneath the hood of Jackson’s ride is difficult to reign in.

“You have to understand your car,” he says. “You have to understand your engine and how it makes power and know what you can get away with. When you see my car out 60-foot everybody, that’s the benefit of a ProCharger; I’ve got horsepower right now. We make eight pounds of boost at the starting line and 32 pounds of boost in three-tenths of a second. But that makes launch RPM even more critical; if I’m a couple hundred off one way or the other it’s up in smoke.

“Air density and track temperature can change so fast that you’ve got to stay on top of it, too, especially if you’re sitting in the lanes for a long time. When I see guys strapped in and not touching anything a mile from the water box, I’m like, ‘What are you doing?’ When I haul the car to the starting line, I’ve got three tune ups written in the computer.”

The lackadaisical nature in which radial tire cars appear to leave the starting line is deceiving. Jackson’s Mustang has been 1.10-flat to the 60-foot clocks, and anything slower than 1.15 won’t support a quality run. “One of the big misconceptions with the radial is that you have to roll it out to get it going and then hit it with power. You can’t take something that weighs 3,300-pounds, ease off the starting line and try to take off and haul ass; the tire won’t accept that kind of shock because the car’s not accelerating fast enough.

“The easiest way to go fast is to do it right now—from the start. That’s why the torque converter is the lifeblood of a radial car; just like the clutch on a Top Fuel car. It has to slip; it has to be smooth. You can have every other component perfect and the wrong converter and the car won’t run.”

He already explained it; it’s a million little things.

This morning, Stevie Jackson and his three amigos— Mike Merritt, Chris Johnson and Brian Glendonious—whom he jokingly refers to as full-time (albeit unpaid) crew members, are already at wide open throttle out in the shop, thrashing on their prized orange Mustang to get ready to go testing. Whether it’s near or far, routine maintenance or backbreaking labor, their level of enthusiasm never changes.

“We love to race,” says Jackson. “We love to travel. If there’s somewhere that’s paying good, we’re going to chase the money. These guys have been with me since the beginning and without them there’s no way we would be able to run like we do. I’m not bluffing; they’ll do anything and they know how it works. They know we can’t race if we don’t win at least some of the time.”

As far as points-earning series are concerned, Jackson has limited options. Most of the series that featured an outlaw drag radial class have folded, but there are independent races all over the country from Las Vegas to Texas to New Jersey. Jackson plans on hitting them all. Determined to run for points somewhere, he’s going to try to run with the National Muscle Car Association in 2012, despite having to run his car in Super Street—a quarter-mile class designed for 33×10.5W-equipped, back-halved, four-link cars with wheelie bars. “To me there’s nothing more impressive, or more fun, than a 3,300-pound street car out-qualifying a 10.5-tire car with wheelie bars. I love it.”

Jackson would probably have a hard time identifying anything he doesn’t love about drag racing, short the unfortunate truth that serious talent and potential don’t ensure a shot at the big time the way it might in other sports. “I think anybody who gets to race is fortunate, so I’m not going to complain. When that thing leaves the starting line, pulls a little over 2Gs, then from a second to three seconds into the run, where we really get after it, pulls almost 3Gs—your vision gets blurry, you’re sucked into the seat—there’s nothing like it. It’s the greatest feeling in the world and money can’t buy it.”

And in the end, Jackson is convinced that Fiscus’ stay on his refrigerator door will be brief. “I’ll tell you this, the next time I go to the race track and stand on the throttle we’re going to go 4.20s. That’ll be the end of that.”

Photographs by Bubba Smoothe, Ian Tocher and John Fore III

This story was originally published on March 26, 2020.