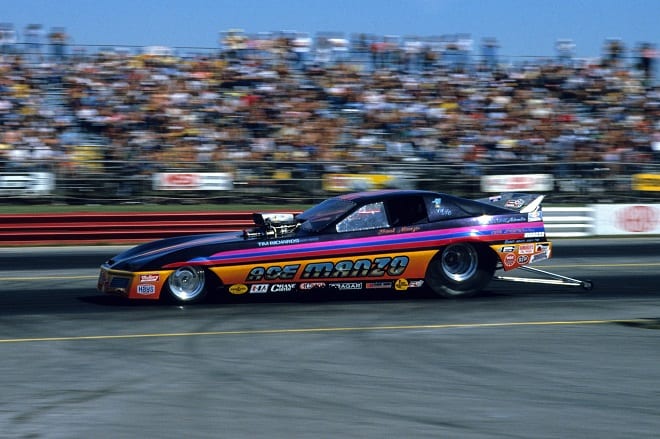

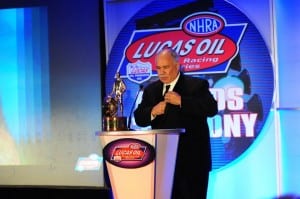

On November 14th, 2011, Frank Manzo took the stage of the Grand Ballroom of the Hyatt Regency Century Plaza in Los Angeles. Drivers, crewmen, team owners and their families were gathered to celebrate, amongst other things, his monumental achievement: the 15th Top Alcohol Funny Car (TAFC) world championship of his career, the seventh consecutive. As he takes to the podium to speak only one problem exists: Frank Manzo doesn’t want to talk about Frank Manzo.

This has become an annual obstacle for Manzo, the virtually mandatory and quite public acceptance of tremendous praise and recognition from the racing world. He was just a kid when he started racing in the mid-1970s—a kid dreaming of winning just one race—who now, at 59, stands before a crowd of his peers accepting yet another championship trophy and check while his name is mentioned in conversations across the room as, perhaps, the greatest of all time.

This has become an annual obstacle for Manzo, the virtually mandatory and quite public acceptance of tremendous praise and recognition from the racing world. He was just a kid when he started racing in the mid-1970s—a kid dreaming of winning just one race—who now, at 59, stands before a crowd of his peers accepting yet another championship trophy and check while his name is mentioned in conversations across the room as, perhaps, the greatest of all time.

He sees it differently than the rest of us, though. He uses words like “luck” and “blessings” and “good fortune” to sum up his success. All of which most assuredly have played a part in this moment, but to a lesser degree than he’s willing to admit. It’s tenacity, talent and dedication—his own, his team’s—that put Frank Manzo’s name alongside that of drag racing’s biggest and brightest, alongside the likes of John Force, Bob Glidden, Warren Johnson, Tony Schumacher.

But when he says, “I don’t do this for attention,” well, he absolutely means it. Humility, especially to this degree, cannot be fabricated, yet there’s more to it than that. It’s not that he’s unaware of his accomplishments or their validity; it’s simply that he’s too damned busy moving forward to spend any time looking back. A moment of reflection would only detract from the time that could be spent working toward doing the things Manzo wants to do, like go fast and win races. This night, though, far removed from the drag strip at this swank black-tie affair, he has little choice in the matter.

“Honestly, a lot of people get mad when I say this, but I think I’ve just been lucky,” he says when recounting nearly four decades of racing, most of which spent absolutely dominating his competition.

“I’m lucky that I can drive a car, tune it, and understand it. We work really hard at it, but I could never dream of this, could never dream of what has happened. The good Lord has taken me to a place that is unbelievable. I get nervous sometimes because I think that someday I’ll wake up and this will all have been a dream.”

The phone rings, and rings, and rings, and finally—Manzo’s voicemail picks up, again. The only recorded message is of him stating his name, “Frank,” in his gruff, unmistakable New Jersey accent.

Seven minutes later he calls back. “This is Frank Manzo,” he says. “Can I help you?”

His tone indicates he’s not real interested in talking, especially at length to someone who’d called from a number he didn’t recognize, and the standard race shop clatter in the background isn’t helping matters. Hustling to load up and head towards Chicago for an NHRA regional event, Manzo suggests we talk at a later date, maybe tomorrow; say, 10:30 in the morning? While I’m appreciative of a scheduled conversation with the man most refer to as “Ace,” it’s looking more and more like a face-to-face interview is the only way to get a proper glimpse into his life, personality and passion. Again, only one problem: the 400 miles between us. What has to be done, however, has to be done.

Upon arriving at Manzo’s pit area at Route 66 Raceway in Joliet, Illinois, amongst a dozen or so other Top Alcohol Funny Cars, it’s obvious that simply being in the same zip code as Manzo isn’t going to make interviewing him any easier.

“Is Frank around?” I ask, walking up to the trailer door.

“Yeah, but he’s not in the greatest of mood,” replies one of the guys on his crew. “He’s on a diet.” Another chimes in: “You could probably get on his good side real quick if you bring a bucket of chicken in there with you.”

Inside the trailer Manzo is staring at a Racepak graph on his computer. He waves me over, points at a stool for me to sit, and turns back to the screen. “Something is going on,” he says. “We’ve got issues with the car; something’s not right; it’s shaking on every run. I’ve got no window with the clutch, period. If I leave 50 rpm different from the run before, it doesn’t go. We’ve been fighting it all year, but I don’t know what the problem is.”

It’s an uncomfortable and somewhat unusual place for Manzo to find himself at this juncture in the race season. He’s been to three national events and has yet to reach a final. He’s made 27 runs and only made it down the track under full power on four occasions. Back in 1972, the struggle he’s enduring this season wouldn’t be anything other than par for the course. But after 200-plus race wins (96 national event, 116 divisional), more than 500 round wins and 15 TAFC world titles, the feeling he has at this moment is unsettling at best—and it would seem to have little to do with his new diet.

It’s an uncomfortable and somewhat unusual place for Manzo to find himself at this juncture in the race season. He’s been to three national events and has yet to reach a final. He’s made 27 runs and only made it down the track under full power on four occasions. Back in 1972, the struggle he’s enduring this season wouldn’t be anything other than par for the course. But after 200-plus race wins (96 national event, 116 divisional), more than 500 round wins and 15 TAFC world titles, the feeling he has at this moment is unsettling at best—and it would seem to have little to do with his new diet.

See, up until this season, Top Alcohol Funny Car drivers could go to eight divisional meets and eight national events and count their best five finishes in each, but now championship points are awarded for seven of a racer’s best 10 national events and three of their best five divisional meets. In order to earn a 16th championship and put together another perfect season (win 7 national, 3 divisional), Manzo will have to sweep his next seven races, as well as win another divisional meet. The only upside to the situation is that Frank Manzo is just the guy to do it.

“I’ve got a very large challenge in front of me to try and fix my race car—let alone try and win the championship,” Manzo says. “If it drives like it does now, I can tell you that I’m in big trouble. In previous years, I came back to win seven, eight or nine races in a row, but I think I was in a different position to do it. Right now, I have to fix the car.

“Everyone thinks that I’m a machine, but I am a human, and now I’m starting to second-guess the way I do things, the way I drive, what I do to the car. Before this is all over, I’m going to have to fix two things: the car and myself.”

Manzo has been there and done that. Having made 3,600 runs in a blown alcohol Funny Car—many of which resulted in a trophy, check, or new record—it’s hard to fathom him literally being stumped. You can see it in his eyes, though, and hear the sincerity in his voice. This is wearing on him.

Born and raised in Matawan, New Jersey, Manzo spent his early teenage years hanging around a Sunoco station down the road from his home, the owner of which had a drag car, a B/Modified Camaro. Within a few years Manzo had made his way for the very first time to Old Bridge Township Raceway Park, just 10 miles from his house. By the time he was old enough to vote, Manzo had his own race car, a ’23 T-bucket with a small-block Chevy that he ran in B/Altered, and he raced nearly every weekend.

“There were a couple of guys out of New York that used to come to Englishtown every Sunday,” Manzo recalls. “They  had little Opels with small-block Chevys in them, I think they called them BB/Altereds, and I always liked that. I started off with an injected small block, then I bought an old fuel Funny Car, a Firebird, and ran that for a couple of years with a blown Hemi. Then in ’74 they made the alcohol Funny Car class, and I’ve been in it ever since.”

had little Opels with small-block Chevys in them, I think they called them BB/Altereds, and I always liked that. I started off with an injected small block, then I bought an old fuel Funny Car, a Firebird, and ran that for a couple of years with a blown Hemi. Then in ’74 they made the alcohol Funny Car class, and I’ve been in it ever since.”

Success didn’t come easy, nor did it come early, but that didn’t dampen Manzo’s desire—it fueled it. His first years were straight out of the struggling race car driver montage.

“I grew up racing around guys like Joe Amato and his Gabriel Hijacker Funny Car,” he says. “The races I went to, there were a lot of cars, a lot of great cars. I was the guy that got his butt kicked by [Dale] Armstrong and all the other guys every weekend. I was the guy getting beat in the first round. It was like that for many, many years.”

But even then, says John Glade, who has been racing with Manzo for nearly 40 years, he was doing everything in his power to find a way to win.

“He’s always been competitive,” says Glade. “Frank feeds off the competition and strives on learning. He wants to know everything about the car, everything there is to know about how it works. He’s always said, ‘This is what we do. We race.’ We’ve always been 100-percent dedicated to being the best.”

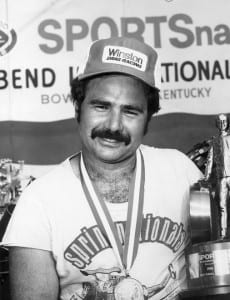

In 1980, Manzo got his first taste of success, winning his first NHRA national event at the long bygone Sportsnationals in Bowling Green, Kentucky, and following it up the next year by winning the first-ever NHRA Alcohol Funny Car championship. Since then, short for a period where he sold his racing operation and focused entirely on his utilities contracting business, Manzo has been a virtually unstoppable force in Top Alcohol Funny Car, winning his second national championship in 1986, then every year from 1997 to 2003 and from 2005 to 2011.

Manzo remembers a time when all he wanted was to win one—just one race. He remembers walking up to Wilfred Boutilier’s BB/Funny Car after he’d won Pro Comp at Englishtown in 1974, touching its fender, looking up at the sky and thinking “Someday.” He’s never forgotten where he came from, but he’s never stopped moving forward, either, and that may be how he’s able to simultaneously treat each win like his first—and his last.

Now, everyone expects it. He’s Frank Manzo; he’s the “Ace.” His dominance has become almost comical, so much so there are pages on the Internet dedicated to “Frank Manzo Facts” (“Frank Manzo is currently planning which races he’s going to … win,” “Frank Manzo’s head gaskets are made of melted-down Wallys,” “Frank Manzo is responsible for more records than fellow New Jersey natives Bruce Springsteen and Bon Jovi,” “The three greatest drag racers of all time are Frank Manzo, Frank Manzo, and Frank Manzo”). He kind of wishes this weren’t the case.

“Let me explain something to you,” he says. “I don’t stop. They had an article about me in the New York Times. I didn’t read it. My wife read it. I don’t have time. I just love to race. I love to climb in that car. I love the challenge. That’s what all this is about. I don’t need it to be where I’m this guy, where it’s just about me.

“But as far as people saying these things, all I can say is thank you. Thank you very much; that’s very nice of you. But I don’t consider myself any different than anyone else out here. I’m very lucky to have my friends, racing friends, speak highly of me.”

No matter the expectations of the outside world, nobody puts more pressure on Manzo than he does himself.

“Nobody wants to do better than I do, and I mean that,” he says. “Every weekend, I want to be the best, and if I lose or have a bad weekend, my phone is ringing with people asking me what happened. They think a part broke or something malfunctioned, but I always tell them the truth: I got my butt kicked! Sometimes the good Lord picks somebody else. I know that at any given time on any given day, they can beat me. There’s no such thing in my vocabulary as an easy round. The only guy I like to run is ‘Bye.’”

Having achieved so much while coming from such humble beginnings, Manzo gets asked a lot of questions, especially from aspiring young drivers. Always encouraging, he has only one angle that he takes when a kid comes up and asks how he drives the car or tunes the car so well. “I always ask them, ‘How many runs do you have?’ They’ll say maybe 120. I’ll just say, ‘Well, you only have about 3,500 more to go and you’ll find out.’”

The expectations, the questions—they’re no worse than what anyone who has reached elite-status in their field, particularly competitive sports, has to deal with. The difference is, Manzo doesn’t embrace it. He doesn’t care to bask in his glory. He doesn’t have a publicist. He makes no effort to cloister himself in roped-off pit stalls, lounges or hospitality tents—not even when given the opportunity—and it’s not because he particularly likes being exposed to the masses, but because to do otherwise would be a step toward buying into the hype, believing that he’s better than the next.

The expectations, the questions—they’re no worse than what anyone who has reached elite-status in their field, particularly competitive sports, has to deal with. The difference is, Manzo doesn’t embrace it. He doesn’t care to bask in his glory. He doesn’t have a publicist. He makes no effort to cloister himself in roped-off pit stalls, lounges or hospitality tents—not even when given the opportunity—and it’s not because he particularly likes being exposed to the masses, but because to do otherwise would be a step toward buying into the hype, believing that he’s better than the next.

Manzo says he’s too superstitious, too serious a believer in karma to be loud and proud.

“I could start talking about 100 national event wins or winning a 16th championship,” he says, “but the next story you’ll write would be about my car not starting. I believe in karma.”

He wipes the sweat from his brow.

“You’re never going to see me doing that dance. I came in this as a young man, just wanting to go and race his hot rod. I’m in here doing that, and when I decide to leave, I’ll go out doing just that.”

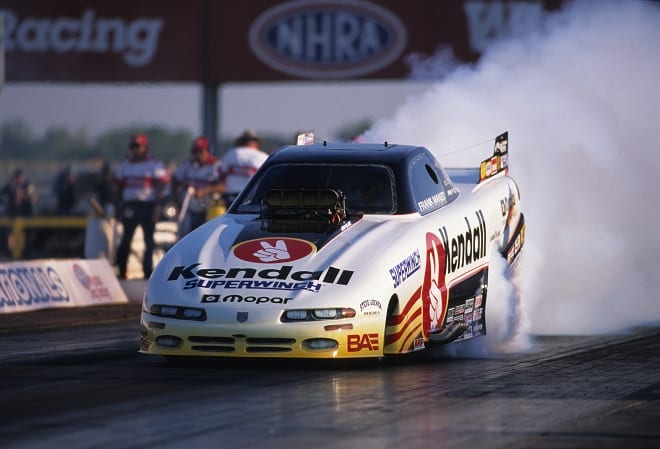

After he jots a few notes down, we head back outside the trailer where his crew—John, Fred, Ed, and Mike—have the Al-Anabi Racing-sponsored Chevy Monte Carlo Funny Car up on jacks ready to be warmed up. It’s nearly 90-degrees here in the pits of Route 66 Raceway under the sweltering summer sun, but that’s exactly what Manzo is after. The race track is going to be hot and greasy and he wants to run the car under some different conditions in hopes of getting it back to where it used to be in terms of consistency and performance. He says there’s nothing wrong with the car; that it’s all on him. That he’s not turning the right screws. It’s hard to accept, but it’s not the type of thing you’d argue with him about.

Interestingly, Manzo refuses to use the word “I” when discussing his success, always mentioning that it’s the team that has achieved so much. (“It’s like football. Yeah, I’m the quarterback; I’m getting all the glory and all the ink. But really, I’ve got seven guys in front of me making sure nobody gets to me. That’s the case with me. I’m very lucky to have the team that I have.”)

When talking about his recent struggles, however, he refuses to place the blame on anyone other than himself; near the polar opposite of how the rest of the population of the planet would handle the situation.

“Between my crew, one of the best in the business, and my wife, I’ve been blessed,” he says. “These guys have been with me forever. And my wife, Michele, oh, forget about it. It’s true what they say, ‘Behind every good man is a great woman.’ She’s been riding down the road with me since 1974. She’s put up with me for a long time. She understands the car, too. If she sees less clutch dust coming out the back of the car on the starting line, she wants to know why. I’m a lucky guy.”

They take the car down off the hydraulic lifts, top it off with fuel and put the carbon-fiber body down over the chassis. There’s a single session of qualifying scheduled for Top Alcohol Funny Car here at this NHRA Division 3 event at 4 p.m. and with any luck, it will be the first step towards Manzo getting his 2012 race season on track. Manzo is convinced the car is most likely going to “jump off the ground again,” but he’s going to keep fighting with it.

“I hadn’t planned on coming here,” he says. “But I’m not going to stay in the shop and sit there trying to figure out why it’s shaking. I’m going to go to the track. I’m going to run the wheels off this thing. I’ve got to fix it.”

Back in the trailer, waiting for the tower to call the blown alcohol floppers to the lanes, Manzo questions himself. “Am I just tired?” he says. “Do I need a couple of weeks off?” He doesn’t know the answer, but he does know that he’s going to keep digging, “a little harder, a little deeper,” until he figures it out.

Manzo’s life has changed amidst all that has happened over the course of his four decades in the sport of drag racing. From struggling to qualify with an old car hauled around on a gooseneck trailer by a dually pickup, to contending for a record 16th world championship with a new car, new sponsor, and a new rig, he’s managed to turn his hobby into his profession. He’s gone from racing almost exclusively at the two tracks local to his home to touring the country racing and traveling overseas to tune other driver’s cars.

And through it all, one thing remains the same: Frank Manzo.

Someday there may come a time when he’s ready to slow down, when he’ll decide he’s done driving, or wants to step away. Right now, though, he’s still having fun and, most importantly, a challenge still exists—a big one. In some ways, this could be the best thing that ever happened to him, the motivation he needs to make history by surpassing John Force as the winningest champion in drag racing.

“Maybe if I feed off this the right way, like in previous years, maybe I can pull everything together and get it going,” he says. “All I can do is keep racing. I might get an ‘F’ for performance, but I’m going to get an ‘A’ for effort. I’m going to do everything I can, just work as hard as I can. We’ve been on a pretty good roll for the last 15 years, so we’re entitled to an off year. I was hoping that year would come around 2020, though.”

Manzo has made his name by coming up big when it matters most—his car has run well when it needed to and he’s driven well when he had to—but facing one of the biggest challenges of his career within a class of competitors as fierce as any he’s ever faced, “Ace” can’t help but think about the early days.

“That’s what it takes,” he says. “It takes competition, it takes obstacles like we’re trying to get past to push you to be better; it makes you work harder.”

It may not be as much fun as running the table, collecting the winner’s share of the purse and some race shop jewelry  for everyone, but Manzo finds reward not in the destination, but in the journey. Again behind the eight ball, with an unhappy race car and slightly shaken confidence, as hard as it may be to believe, Frank Manzo may well be at his absolute best.

for everyone, but Manzo finds reward not in the destination, but in the journey. Again behind the eight ball, with an unhappy race car and slightly shaken confidence, as hard as it may be to believe, Frank Manzo may well be at his absolute best.

“When it’s time to lift up our heads and check the scoreboards,” he says, “we’ll do it.”

As the sun starts to set on Joliet’s spectacular quarter-mile, the last pair of Top Alcohol Funny Cars, Manzo and Chris Foster, roll through the water box. The old master hits the throttle and the Hoosiers start to smoke, while in the opposing lane Foster’s car shuts off unexpectedly, giving “Ace” the race he enjoys most—the one against himself. In 5.606-seconds it’s all over, a bit of order restored to the universe. Number-one qualifier: Frank Manzo.

Well, Frank, it’s okay to look now.

(Photographs by NHRA/National Dragster, Mark J. Rebilas, Roger Richards and Khalid Saif)

This story originally appeared in Drag Illustrated Issue No. 67, the Sportsman Issue, in July of 2012.

This story was originally published on December 3, 2015.