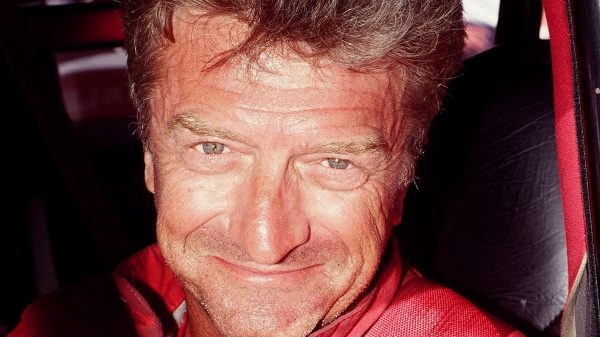

Regardless of the sport, truly great athletes share an innate feeling they were put on this earth to ultimately dominate their opponents; they believe deep down inside that winning is their just reward.

Thomas Steven Jackson believes.

But belief is not nearly enough. Success comes to those who bolster their belief with a regimen of diligence and hard work; who demonstrate a commitment to sacrifice and taking action toward reaching their goals.

Steve Jackson is committed.

Goals are relative, too. There’s no end of competitors aspiring to be among the best at their craft. Few, however, harbor the overwhelming desire to actually be the best.

“Stevie Fast” is filled to the brim with desire.

“I drive with my hair on fire all the time,” he says. “When I get in that seat, there’s no tomorrow every single run. And that sounds over the top, but it’s the way I feel about it. I mean, even test runs, I take it seriously. I love it. It’s what I do. I mean, I don’t want to say it’s what I live for, but it kind of is. All I’ve ever wanted to do is race.”

Jackson’s career took off when he made his way to Qatar late in 2012, accompanying the Procharger-equipped, big-block-Chevy-powered ’93 Mustang he’d just sold to Al Anabi Racing team owner Sheikh Khalid al Thani. Despite al Thani’s extensive ADRL and NHRA involvement, Jackson insists he’d never even heard of the sheikh before receiving a call from him that fall with an essentially open-checkbook offer for what was then the fastest small-tire car in the world.

Jackson’s career took off when he made his way to Qatar late in 2012, accompanying the Procharger-equipped, big-block-Chevy-powered ’93 Mustang he’d just sold to Al Anabi Racing team owner Sheikh Khalid al Thani. Despite al Thani’s extensive ADRL and NHRA involvement, Jackson insists he’d never even heard of the sheikh before receiving a call from him that fall with an essentially open-checkbook offer for what was then the fastest small-tire car in the world.

“I was kind of dumb to that whole world,” Jackson admits. “Racing is a small circle, but really, you’ve got fuel cars, then you’ve got door cars, Pro Mods, and then you’ve got small-tire guys, which is what I was, and everybody kind of stays in their own little world.

“So they buy that thing and they wanted me to come over and just kind of show them how to run it. Well, when I started it up in the shop, it was so loud and obnoxious that they couldn’t even stand around it. It cleared the whole shop out. I mean, that thing was hateful; on true 29s at 3,200 pounds it went 4.20s, so it was a handful. I told them, if you care about somebody, you probably don’t want to start them out in this. You’ve got to ride this horse. This is not something you just ease on down the race track.”

That led to Jackson being tapped as the car’s continuing driver and opened his tenure as an official Al Anabi Racing team member. He wound up winning the Arabian Drag Racing League Super Street championship that year with the Mustang on true 10.5-inch slicks, but it really wasn’t enough to keep the always-on Jackson busy and satisfied. Hanging out amongst the likes of Shannon Jenkins, Mike Castellana, Todd Tutterow and Frank Manzo day after day at the Qatar Racing Club gave him his first up close and personal look into Pro Mod racing—and he liked what he saw.

Meanwhile, Jackson’s relationship with al Thani strengthened to the point he told KH, as all the sheikh’s closest friends called him, that he eventually wanted to try his hand at driving a nitrous-boosted Pro Mod. Coincidentally—or maybe not—about the same time al Thani approached versatile tuner Billy Stocklin, (who was on hand in Qatar helping Manzo win the Arabian Pro Extreme championship with driver Alex Hossler that year), about giving him a new project, too.

Stocklin recalls al Thani and driver Khalid al Balooshi, who ran ADRL Pro Nitrous before becoming an Al Anabi Top Fuel pilot, approaching him with an offer to run a turbocharged Pro Mod entry.

“I told them I was not interested in doing that, so they asked if I would do a nitrous car again and I said, yeah I’d be into that,” he says. “Then they asked who I would want to drive it. Well, it’s kind of a short list of who’s available over there, so I said Stevie was my first option because I knew he had a super-good work ethic and was a really good driver.

“It came to pass that KH and (Don Schumacher Racing Top Fuel crew chief) Phil Shuler were pretty good friends at the time and I’m fairly certain now that Phil was kind of stirring the pot in the background to put me and Stevie together,” Stocklin adds. “They kind of put the right options in front of me and let me feel like I picked them myself. I mean, obviously I had some influence, but I think that Phil, who I now count as one of my very best friends, kind of set the stage and went out of his way to help us both out a lot—but especially Stevie.”

“It came to pass that KH and (Don Schumacher Racing Top Fuel crew chief) Phil Shuler were pretty good friends at the time and I’m fairly certain now that Phil was kind of stirring the pot in the background to put me and Stevie together,” Stocklin adds. “They kind of put the right options in front of me and let me feel like I picked them myself. I mean, obviously I had some influence, but I think that Phil, who I now count as one of my very best friends, kind of set the stage and went out of his way to help us both out a lot—but especially Stevie.”

In the end, Jackson and Stocklin got the nod from KH to resurrect the ’69 Camaro in which Balooshi had delivered the 2009 ADRL Pro Nitrous world championship to Al Anabi. Jackson admits to being more than a little surprised at the trust extended by his powerful new friend.

“I had zero experience with a Pro Mod at all. I had gone and got my NHRA Top Alcohol Dragster license at Frank Hawley’s school, so I had driven some stuff with some power, but never a door car with real power and I’d never messed with a big nitrous motor before. The biggest nitrous engine I think I’d ever worked on at the time was a five-inch bore space 762, so I think he was kind of foolish to put me in that thing, to be honest.

“But it worked out,” Jackson says. “I got to hanging out with Billy over there and that was cool. I had raced against him before in the States, but I never really knew him, but KH put me and Billy together and said, ‘Alright, you guys take this old raggedy car that nobody can get down the race track. It’s got thousands of runs on it and the body is falling off of it, but see what you can do.’”

The deal was if Jackson and Stocklin could get the admittedly well-worn Bickel-built machine into the 3.70 zone—which no one else had even come close to over the years—al Thani would ship the car back to the U.S. for a fully financed run in the 2013 ADRL Pro Nitrous season. The carrot was hung from the stick, so Jackson immediately set about going after it in a car he nicknamed “Honey Badger.”

“We went out there and spent about two weeks just tearing that thing to pieces,” he says. “We took everything off it but the body. Changed everything. We didn’t have free reign, but we could use pretty much whatever used stuff they had laying around and they had a lot of good, used parts just laying around back then. And KH did let me order a little bit of new stuff, too.”

Stocklin mostly remembers that time as a blur since his priority remained the screw-blown Camaro driven by Hossler and he basically had to assume a second full-time obligation in order to run Pro Nitrous with Jackson. He describes showing up at the track about 6 o’clock in the morning and working alongside Jackson until 9 or 10 a.m. before heading over to the Manzo-Hossler camp during the day.

“I would come back and check in with Stevie at lunch time and somewhere around 6 or 7 at night those guys would wrap up on the blower car and me and Stevie would stay and work until 1 or 2 o’clock in the morning,” Stocklin says. “Every morning. Then we’d go back to the hotel and get three or four hours of sleep and we did that day after day, week after week.”

Stocklin freely admits it was a frenetic schedule he probably wouldn’t have tackled on his own. “You know, it’s not just that he doesn’t stop, but Stevie motivates everyone around him to work like that. Normally I’d have a difficult time keeping that pace up, but he’s just like the Energizer bunny and keeps you going.”

One of the first changes they made was to install an automatic transmission in the car, but most of their efforts centered on shedding excess weight.

“I mean, we did silly, retarded stuff trying to get it light because it was kind of heavy and there was no minimum weight limit over there. The lighter you could get it, the faster it would go,” Jackson reasons. “I told Billy, ‘Alright, I’m going to use a hundred zip ties on the whole car; that’s all I’m going to use because I don’t want to weigh it down with any more.’

“And we did all that and it still would not go 3.70s for us. We beat on it for four straight weeks, and it would run 3.80 flat, 3.80 flat, 3.80 flat. It would not go .70s. I mean it got to the point where I’m eating one meal a day just so I was as light as possible, too, but it just would not go any faster.

“So the last race of the season over there I strip completely naked under my fire suit. I was like, this is all the weight that’s left to be off of it. This is a true story now; I was completely buck naked under my fire suit. Didn’t eat nothing that day. And we went out there and it went a 3.79 with a seven or something like that. And Billy’s at the end of the return road, hugging me and stuff. And it’s hot, because, Qatar, you know? He’s like, ‘Why don’t you take your fire suit off?’ And I say, ‘Well, I can’t, I’m going to have to wait ‘til I get back to the shop.’

“But we finally did it, we ran the 3.70 and KH gave us our deal and we came over and raced ADRL and actually won the Pro Nitrous world championship in 2013 with that car. How’s that for a storybook ending?”

Dubbed “Stevie” by his family to more easily identify him from his dad, Tommy, Jackson grew up in tiny Hephzibah, Georgia, a little southeast of Augusta, not far from the South Carolina border. Among his earliest memories is riding shotgun with his dad as a three year old, on their way to participating in local street races.

Dubbed “Stevie” by his family to more easily identify him from his dad, Tommy, Jackson grew up in tiny Hephzibah, Georgia, a little southeast of Augusta, not far from the South Carolina border. Among his earliest memories is riding shotgun with his dad as a three year old, on their way to participating in local street races.

“Everybody raced on the street back then. This would’ve been about ‘83, ’84; I was born in 1980,” Jackson says. “I’d get to help test out the nitrous and stuff on the way. I mean, he had nitrous on his cars before anybody had nitrous. It was cool. And not only did we race on the street on Sundays, but we would go to the race track on Thursday nights, Carolina Dragway over in Jackson, South Carolina, every single Thursday night they were open and match race. That’s their grudge night.

“My dad always worked on cars, he was always tinkering with them. So that’s kind of where I think it bit me really early. I mean, by the time I was five, I wanted to be a race car driver. I liked NASCAR for a little bit, but then probably by the time I was six or seven I wanted to drag race. I wanted to run a fuel car. As long as I can remember, ever since I saw my first fuel car, that’s what I’ve always wanted to run.”

Considering the closeness with his father, Jackson admits it hit him hard when his parents split up and divorced when he was four years old, calling it “a real eye opener,” even at that early age. Yet, he also considers himself “blessed” by his mother soon remarrying a tough-as-nails truck driver named Ronnie Milliken. “A good man and a good role model,” Jackson says. “He didn’t take any crap; beat us regular. So it was good. Good for me.

“He treated us like we were his kids, me and my brothers and sisters, helped raise us,” Jackson continues. “But he was into NASCAR. We watched NASCAR on Sundays and that’s kind of where, early on, I kind of wanted to maybe drive one of those silly NASCAR cars just because he liked it so much. I had just got into drag racing more serious when he passed away from lung cancer in 2000. Wish he was still here. He would love what we do now.”

Jackson’s first official time down a race track came in 1996 at Carolina Dragway, back when the “House of Hook” was still a quarter-mile facility. He was 16 years old and driving an ’88 Camaro his father gave him with a 2.8-liter V-6 under the hood. “It looked like a sports car, but it ran like a minivan,” he laughs.

“I’ll never forget it; it’s like it was yesterday. I snuck to the race track on a Thursday night and when I signed in at the waiver, I was scared to death,” Jackson recalls. “I didn’t really know anything about drag racing, so I didn’t know if they would announce my name or if it would be in the paper. So I went there with my friend, Joe Davis, and I signed in with my first name and his last name. So for my first pass on the waiver sheet my name was Thomas Davis. And I took that Camaro out there and ran it 13 times that night. The fastest it would go was an 18.20; that’s all it would run, quarter mile, foot on the floor, going I don’t know, maybe 70 or 80 miles an hour.”

Regardless, Jackson was hooked. He took the car home that night and immediately started cutting the seats out of it and looking for any other extra weight he could easily discard. Still a high-school student at the time, he also worked two 40-hour-a-week jobs bagging groceries at two different supermarkets.

“One of my jobs was at the Winn-Dixie and I remember getting my paycheck on Friday after leaving the race track the night before and going to AutoZone, which was right next door, and spent my whole paycheck, probably a hundred bucks or so, in the performance aisle. I didn’t even get out of the parking lot before it was all gone,” Jackson says. “I bought a fuel filter, a K&N air filter, some rocker arms or something like that and some wax. Just about anything they had that I thought would make it go faster. Went to the track the next Thursday and picked up over four-tenths of a second.

“It went 17.70-something and I was like, this is going fast. I thought it was going to be easy. So I raced that thing every time the track opened. I mean, it had a single traction rear end, but it would do a burnout in the water and I would burn the back tire off every time. Then I started to take my mom’s minivan to the track and put nitrous on it. Anything that would run, I would take it to the race track.”

Shortly afterward, Jackson left grocery bagging behind and picked up a better-paying job at Smith’s Chevron in Augusta, where he honed his mechanical skills. By the time he turned 20 Jackson was a factory-certified master technician for Ford, GM and Suzuki. “I never went to school to be a technician, but I always had good mechanical ability and I’m meticulous and I kind of just learned and taught myself,” he says. “Really, everything I’ve ever done I’ve been self-taught. I’m not so proud of that; it’s just that I work with what I have and I try to make the most of everything.”

Shortly afterward, Jackson left grocery bagging behind and picked up a better-paying job at Smith’s Chevron in Augusta, where he honed his mechanical skills. By the time he turned 20 Jackson was a factory-certified master technician for Ford, GM and Suzuki. “I never went to school to be a technician, but I always had good mechanical ability and I’m meticulous and I kind of just learned and taught myself,” he says. “Really, everything I’ve ever done I’ve been self-taught. I’m not so proud of that; it’s just that I work with what I have and I try to make the most of everything.”

Jackson adds he learned about a lot more than just fixing cars at the service station—even if he didn’t fully realize it while it happened.

“You know, you look back at your life and I worked there for probably four or five years and that probably gave me the best education in life that I ever had, everything about business and life. I worked for a guy, Tommy Smith, who was a very good businessman, and Tim Taylor, who kind of ran the place. Both of those are very good businessmen, but they cared enough about me and other people that worked there to kind of, during an impressionable point in your life when you’re in your late teens and early 20s, make decisions that’ll affect the rest of your life,” Jackson explains.

“They taught me how to treat people, how to be honest in business and how to deal with customers. And when you can deal with customers at that age; I mean, we were plugging tires and changing oil and pumping gas and seeing how they ran that business, it affected me probably even more than what they realized.”

To this day Smith has never seen Jackson race, but Taylor used to help out with Jackson’s first real race vehicle, a clapped-out S-10 pickup he literally rescued from a wrecking yard.

“We would tow that raggedy S-10 truck to Jackson (SC) with Tim’s Ford truck. We would work all day at the Chevron and then me and him would load it up and haul it to the race track. He nicknamed it “The Cockroach” because it was two different colors of primer, not even different paint, just primer. It was so raggedy,” Jackson repeats. “It had an old 327 in it, but it was pretty fast. It ran 14s on the street and we had to finally quit running it quarter mile when it got into the eights. But before I quit with that, it almost ran four seconds on leaf springs in the eighth mile and it was a legitimate street vehicle.

“That was in 1998, ’99, when 5.20s and .30s was fast. We won a lot of grudge races with that thing. I mean, we’d run it four or five times a night for 50 or a hundred bucks a run. Back before technology took over, racing was much more grassroots. The same people that do it now did it then in the match racing scene around here, but everything was slower. People would run for smaller amounts of money. It was nothing for me to run six times a night. Now, you’re lucky to match race six times a year. But then it was for $50; now it’s for $20,000 a race. So the stakes are a lot, lot higher.”

Jackson insists that cutting his drag racing teeth on the grudge scene has benefited him throughout his entire racing career. He’s convinced grudge racing makes a driver a better, more composed racer.

Jackson insists that cutting his drag racing teeth on the grudge scene has benefited him throughout his entire racing career. He’s convinced grudge racing makes a driver a better, more composed racer.

“Not only do you have to learn how to deal with people and negotiate, but you get to feel a pressure early on in your life when you’re racing that you never can feel until you get far advanced in the pro stuff. Every grudge race, whether it’s for $50 or $500 or $5,000 is like going to the final round, every single one,” he stresses.

“There’s been many times where I’ve raced for all the money that I had in my pocket. You’d go grudge race and run for 300 bucks and that’s your paycheck back then. So if you can sit on the starting line and bet every quarter you have and have to win that round just to have gas money to go home, going out there and running E1 at a PDRA race now, from a pressure standpoint, it’s pretty easy. You learn how to deal with it. I’m very grateful to have come from a match-racing background.”

By the early 2000s Jackson had a 588-cubic-inch big block in the S-10, but also realized he’d more than reached the limit of its chassis, so it was sold in favor of purchasing the rolling chassis of a stock-suspension, Fox-body Mustang. With the truck’s new engine and transmission installed, the car went 5.21 on its first pass.

That kind of performance merited a real paint job, Jackson reasoned, so that car became the first to sport his signature orange hue. “I’m a Georgia Bulldog fan, so we actually hate orange, but the guys that paint all my cars, Neil and Van at 2 Keys Customs in Augusta, they kind of surprised me and went ahead and painted it orange. I walked in there and it blew me away. It looked awesome. I was like, that’s a good-looking race car, so I don’t know, it just hooked me. The orange picked me. It’s like every good thing in life; everything that’s kind of special ends up picking you.”

Jackson says he won a lot of money with the new car, which soon was running consistently in the fours. It also delivered his first serious crash, taught some valuable lessons and helped create his “Stevie Fast” persona.

“We were at Carolina Dragway and it was on the bumper for about 400 feet. I could look over and see that I was winning, so I stayed in it foolishly and blew it over like a drag boat,” Jackson describes. “I mean, it was a terrible wreck. It slid on the roof upside down on top of the wall and spun around. But it looked way worse on the outside than what it was on the inside. Most of them do.

“We were at Carolina Dragway and it was on the bumper for about 400 feet. I could look over and see that I was winning, so I stayed in it foolishly and blew it over like a drag boat,” Jackson describes. “I mean, it was a terrible wreck. It slid on the roof upside down on top of the wall and spun around. But it looked way worse on the outside than what it was on the inside. Most of them do.

“Luckily, I was pretty much uninjured, but I was just wearing jeans and a T-shirt with a helmet on at the time. So that was a rude awakening to me. I bought a fire suit and some driving gloves after that one,” he says. “But it also kind of cemented my personality in the racing community. People were like, we don’t know who this kid is, but this guy is crazy. They could kind of see my true passion for the first time.”

The car was a total loss, but just six weeks later Jackson had taken a stock Mustang and built a new race car from the ground up. “It was painted orange, exactly like the other one, so a lot of people thought we had just fixed the old car,” he says. The new car progressed from carrying a big-block, conventional-head motor to a Big Chief set up to a big nitrous motor to a ProCharger-boosted engine when in addition to match racing Jackson won the 2008 ORSCA EZ Street championship. “I probably logged thousands of laps in that car, ‘til it was just completely wore out,” he says.

That’s when, in 2010, Teddy Houser built the car in which Jackson basically redefined drag radial racing before sending it overseas to the Al Anabi Racing stable. “I think we were the first to the 4.70s with it; I know we were the first to the 4.60s and the first to the 4.50s. We were the first to the 4.30s and we were the first to the teens in that thing. So we did a lot with it,” Jackson points out.

“That car I guess helped me grow into who I am today because we also lost a lot with that thing. I was very stubborn and wouldn’t take help really from anybody, so I had to learn how to tune it on my own. I learned how to run the car by myself and by doing that then, it enabled me later in my racing career to be able to run my own car now.

“Driving is, I don’t want to say it’s the easy part, but it’s the smallest piece of the puzzle in one of these things. Ninety percent of race wins are won at the shop; 90 percent of everything you need to do well at the race track happens there. And learning that, learning how to run a car, make calls and have the guy that makes that decision when it’s time to go up to the starting line, it really has helped me. I enjoy that as much as I do driving. Tuning and running the car and running the team is what I’m good at.”

That drive, that desire, that dedication to doing whatever it takes to be the best caught Phil Shuler’s attention in 2007 when he and Jackson frequently crossed paths at race tracks throughout the Southeast. Shuler, currently co-crew chief for Spencer Massey’s Top Fuel entry, was already eight years into his NHRA tuning career by that time.

“I used to drive a bunch of grudge cars but once I got into racing as an actual job I kind of figured out it wouldn’t do me a lot of good to get hurt in a race car, so I decided to let someone else play and have the fun,” Shuler says. “I had been watching Stevie and how he did things at a few races and saw just his sheer determination. One thing he has that’s the exact same as I have towards racing is that he hates losing even more than he likes winning. We refuse to lose, I guess is how that goes.”

That shared perspective worked in Jackson’s favor shortly after he’d earned his Top Alcohol license in ‘07 and began trying to secure a Top Fuel ride for the next year. He had a little success in stirring up interest and funding, he says, when Carolina Dragway owner Jeff Miles contacted Shuler on Jackson’s behalf and asked if he could make it possible for Jackson to meet with “The Don.”

“So Phil set that deal up, kind of before he knew me really, I guess he had heard of me—maybe,” Jackson says. “Anyway, I went up and met with Don Schumacher, this was in 2008, and kind of got my eyes really opened to the business side of fuel car racing. Up until I went up and met with him I knew a little bit about it, but I didn’t realize it was so business driven and so little about what you are as a driver. Before then, I thought if you’re a good driver, if you’re the best there is, it would be just like football, right? You get to go play in the NFL. Well, I realized it’s not like that at all. It doesn’t really matter how good you are if you don’t have funding. And that was an eye-opening experience for me.”

Schumacher was cordial, informative, even encouraging, Jackson says, but also made it perfectly clear he still had a long way to go.

“I kind of decided right then that I was not going to bother Don again until I had secured enough funding. I’m not going to call him up every week and be like, ‘Hey, I’m still working on getting money.’ But if it ever unfolds to where I can get funding to run a fuel car, I’m just going to call him up and tell him the check is on the way.”

For now, though, with Stocklin as his crew chief, Jackson will concentrate on going after the 2015 PDRA Pro Nitrous championship with the new Reher-Morrison-powered ’69 Camaro he took delivery of from Jerry Bickel Race Cars late last summer. Full-time crew member Jack Barbee and part timers Chris Johnson and Robbie Lowry help Jackson operate out of a shiny new shop behind his home in Evans, Georgia, where they also maintain “The Shadow,” Shuler’s now-screw-blown ’93 Mustang back-halved grudge car in which Jackson won the marquee Radials vs. The World class early this year at Lights Out 6 in Valdosta, Georgia. Additionally, Jackson’s Killin’ Time Racing maintains the 2000 Camaro grudge entry of team sponsor Jeff Sitton of SEI Oilfield Services in Ft. Worth, Texas.

For now, though, with Stocklin as his crew chief, Jackson will concentrate on going after the 2015 PDRA Pro Nitrous championship with the new Reher-Morrison-powered ’69 Camaro he took delivery of from Jerry Bickel Race Cars late last summer. Full-time crew member Jack Barbee and part timers Chris Johnson and Robbie Lowry help Jackson operate out of a shiny new shop behind his home in Evans, Georgia, where they also maintain “The Shadow,” Shuler’s now-screw-blown ’93 Mustang back-halved grudge car in which Jackson won the marquee Radials vs. The World class early this year at Lights Out 6 in Valdosta, Georgia. Additionally, Jackson’s Killin’ Time Racing maintains the 2000 Camaro grudge entry of team sponsor Jeff Sitton of SEI Oilfield Services in Ft. Worth, Texas.

It’s a busy place, but with plenty of room to fit a 300-inch wheelbase Top Fuel dragster—should the need ever arise.

“I’ll be honest; right now to me, it feels like that’s an unattainable dream, but sometimes I think it’s way closer than what I think, if that makes sense. I made my mind up three years ago that I’m very blessed to be doing what I’m doing and I’m extremely happy racing what I’m racing. And if I end up racing these things that I’m racing for the next 20 years, I’m okay with that. I am not going to kill myself over obtaining $3- or $4-million a year to hand over to someone to drive a fuel car. I kind of made my mind up that if I am destined to drive one of those, it will happen,” Jackson says.

He realizes, though, it will take the right sponsor with the right attitude and a willingness to operate outside the current corporate norms in order for a partnership to work.

“They’re going to have to accept all of Stevie Jackson,” he stresses. “What racing is missing right now is rivalries; that’s what’s killing it. They’re not going to get me on the top end with my Mello Yello hat on saying thank you, I just want to appreciate all the sponsors that supported me and the crew did a good job. I’m going to tell you that I just slapped that guy or girl around that was in the other lane and they need to go back and work on that junk and have it ready for the next race. And a lot of team owners can’t handle that.

“I just wish more people would speak their mind and I wish it would be less polished than what it is,” Jackson continues. “People don’t want polished product. TV networks want polished product; people that spend corporate dollars want polished product. But the fans want the raw deal. It’s just like life. I mean, it’s passion. Passion is what drives this thing. And if it’s going to get better, if Stevie Jackson is ever going to make it in a Top Fuel or Funny Car, it’s got to be passion driven.

“My sponsor right now, Jeff Sitton, he and I have the same mindset. The first thing he told me is ‘I don’t want to recreate you; I don’t want to change you; I want you to be you.’ He said to tell it like it is. He said, ‘You get down there on the top end and they’re doing an interview and you want to say something, you say it. You speak what’s on your mind.’ And that’s why we work very well together.”

Those who know Jackson best, both as a racer and a personality, wholeheartedly agree he has what it takes to be a star in drag racing—if only his star is allowed to shine.

“Stevie will make it farther than I can take him. He’s got the skills; he’s got the big, flashy smile; he’s got the big interviews; he’s got it all. I can help him get to about where we’re at with the nitrous cars; I can help him with a blower Pro Mod, but after that I’ll be left behind,” Stocklin declares with absolutely no trace of self pity or bitterness. He’s a factual guy and it’s just the way he sees things. “There’s no doubt in my mind about Stevie’s potential.”

Likewise, Shuler believes Jackson could bring a much-needed breath of fresh air to what he feels has become a somewhat stale atmosphere in the sport’s highest echelons. He suggests the politically correct crowd has robbed drag racing of much of its color and drama.

“Everybody wants to make sure they say the right things and make the right gestures and really it shouldn’t be that way. Everybody should have their own personality and if you don’t like that guy you should be able to say you don’t like that guy,” he says. “Stevie could be a great spokesman; I just don’t know that he could ever fit the scripted-interview, PC-policed theme. You can’t make people be something they’re not, and I give him credit for always being himself. No matter what, whether the car runs good, bad, or just plain sucks, what you see is what you get with Stevie.”

For his part, Jackson is willing to bide his time, confident in the belief that his time will come, one way or the other.

“I want to drive a fuel car so bad I can’t stand it sometimes,” he states. “I told Phil the other day, one of two things is going to happen: I’m either going to get a ride driving one or I’m going to be a hundred years old and finally making enough money to drive one of my own and I won’t be any good at it anymore. But I’m still going to drive one before I die.

“And I don’t care whether it’s Top Fuel or a Funny Car. To me it doesn’t matter; I just want to drive the fastest accelerating stuff on earth. As long as it’s got nitromethane in it, I’ll drive it. Except for a boat; I don’t care anything about those nitro boats. That’s crazy.”

This story was originally published on September 29, 2015.