It all began rather innocently, probably while he was a young teenager changing oil at the family’s Pontiac dealership.

Richard Maskin had yet to have an official Michigan state driver’s license but that didn’t stop him from driving cars in and out of the dealership garage. And it certainly didn’t stop him from day-dreaming of cars. But it all began even more innocently when he did receive his driver’s license with his first car a 1962 Corvair convertible he chose off the dealer’s lot.

It might have begun rather innocently in this two-car garage behind his house in Michigan, but the beginnings of Dart actually were formulated in the mind of one Richard Maskin.

And a date which found him taking a girlfriend to Detroit Dragway was all it took to cement a life which has culminated in the business known as Dart Machinery, a company dedicated to the manufacture of race related cylinder heads and blocks. A company which most likely this year will cast, machine and sell roughly 7,000 blocks and over 25,000 heads. With a product line that ranges from the popular Chevrolet models to Fords and others, Dart Machinery has made quite a name for itself in the industry, a name that was built on the ideas most likely rolling around in the head of Richard Maskin as he changed oil, eventually going on to quite a career as both a drag racing driver but most notably a championship engine builder.

Maskin says, “My first real race car was a ’55 Canadian Pontiac. I bought that car for $25 and it had to be a Pontiac because of our dealership, but the Canadian models came with Chevy engines. I had been working on my friend’s small block Chevys so that was what I wanted. I turned that car into a C/MP class car and I remember having to explain to the NHRA Tech guys that Canadian Pontiacs had Chevy engines.”

That might have been Maskin’s first foray into the world of NHRA Tech but it certainly wasn’t the last.

With his attendance at Northwood University, Maskin not only gained an insight into the business world, but he also befriended a fellow racer Mike Keener. “Keener and I eventually built a ’68 Camaro and turned it into a Modified Production car. Keener got drafted into the Army and I didn’t really have enough money to campaign the car on my own so Keener sold his interest to Jim Gilbert and the Mouse Pack car became the fastest C/MP car in the country back then.”

By the 1970s, Pro Stock was taking the drag racing world by storm and Maskin’s Camaro looked every bit like the Pro Stock cars of the day except for the small block engine under the hood. “We thought about running Pro Stock but I couldn’t afford it on my own,” Maskin said.

Lo and behold though, American Motors had decided to throw their hat into the Pro Stock arena and hired an ex-Ford employee by the name of Bob Swaim to run the program. Swaim convinced Ford racer Dyno Don Nicholson to switch to American Motors, a move that was later rescinded when Ford upped the ante to Nicholson.

“I had made a call to Swaim earlier and it opened the door for a small deal for me,” Maskin said. “So I sold the Camaro and began building the AMC. When Nicholson turned down the offer, Swaim called me but I couldn’t do what they wanted however, I turned them onto Wally Booth and Dick Arons who were building a Vega at the time. That’s how the AMC deal came to be and I got a small deal with it.”

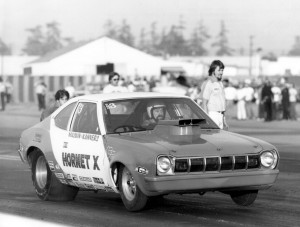

A quick learner, Maskin eventually built an AMC Hornet with some assistance from AMC and then new partner Dave Kanners. Now building his own engines, Maskin took the AMC cylinder heads, cut them up and added an aluminum plate where the intake ports were.

With racing always on his mind, Maskin eventually found his way into the world of Pro Stock in the early ‘70s. It was his understanding of air flow and ability to cut and massage cylinder heads which led to the success of the AMC racing program and eventually to Dart itself.

Maskin said, “Back then, nobody had a flow bench. Smokey Yunich did and he originally did some AMC heads. We then looked at them and using the stock cast iron AMC heads, we literally cut the top of the head off right down to the spring seats. We then fabricated an aluminum plate that we bolted to the casting and cut new intake ports that moved the port up one inch from where it was. We made our own set of shaft-mounted rockers and where the Chevy guys were moving the pushrods over .100” or so to clear their ports, we moved our 3/4”. We didn’t know anything about short turns, longer valves, or bigger valves. We just moved the port up to gain a better line of sight into the port.

“The only problem was that where the aluminum plate met up to the cast iron in the rocker area, we couldn’t stop oil from leaking through into the intake port. We finally made a cast iron plate for the next set and furnace brazed it to the head. But we didn’t stop there. We went after the exhaust port too, changing that design to a D-shaped port. It was quite a bit of work. It would take about a whole year to build a set of heads.”

By that time, Swaim had been replaced by Bob Wheat. Maskin says, “I had gone to college with Wheat so I called him and told him I wanted to build my own head and that I was going to approach New Haven Foundry and I wanted Wheat to at least corroborate with them that I wasn’t just some fly-by-night guy.”

New Haven Foundry (no longer in business) had some cobbled up tooling that Maskin took and with the help of Gary St. Denis whose uncle owned a pattern shop in Canada, they changed the tooling to look exactly like the heads they had cut up and fabricated. All done with the blessing of American Motors.

Maskin said, “When you let the clutch out on that engine, stand back because that car just flat ran. A year or so later, I ran out of money and I walked in the back door of Midwest Auto Parts, which is where Dick Arons and Wally Booth built their engines, carrying one of those heads. Arons asked ‘What the f*$# is that? And do you have any more?’

“I have as many as you want,” was Maskin’s comment. “And that’s where the beginning of the knowledge to do all of this started. We then went on to do some small block Chevy heads when I partnered with Andy Mannarino and they started to run just like the AMC stuff did.

“It’s always been my position,” he says, “that you could burn my shop to the ground but you’re not going to take away the knowledge I have to make things better.”

With the energy crisis hitting hard in the ‘70s, the AMC deal dried up and it became apparent that racing was going to have to be put on the back burner for Maskin. “I had a family, two daughters Tricia and Bridgett, and there were things which were more pressing than racing so I went back to work fixing cars,” he says, “This was during the times when emission systems on cars were beginning and I knew how to fix that stuff. But finally, and I mean it, God brought this whole Dart thing to me. I was having lunch at a deli one day and I meet Arthur Cousins, A.K.A. Art the Dart.”

Cousins was the equivalent of a Funny Car groupee. He would hang around the Funny Car pits at the time and sometimes travel with some of the racers. Cousins knew that Maskin had done some pretty extensive head work and it was his doing that allowed the AMC cars to run as fast as they did.

Cousins’ family owned a company that supplied tank components for the military and they were looking for some consultation help with their business. Maskin obliged and in the course of helping from a business perspective, Cousins asked if he’d like to go to a local track where the Funny Cars were running. Cousins had befriended Billy Meyer who was there for a match race. During the course of the day, Maskin was asked to look at the cylinder heads.

“Back then,” Maskin said, “the Funny Cars ran cast iron heads and the dragsters ran aluminum and while they had intake ports that were supercharged, the exhaust ports wouldn’t work on a lawn mower engine. I was flabbergasted. Back then, part of the reason the AMC stuff ran so good is that we really paid attention to air and fuel flow characteristics. And it’s the same reason our stuff today runs so well.

“There are lot of misnomers going around and one of the fallacies in this business is that the exhaust side of the head doesn’t matter much because it’s always under pressure,” Maskin said. “Airflow into the engine doesn’t matter much if you can’t get it out. Naturally, both sides of the head are important though.”

This, of course, was 1981 and there were no specialty cast heads or billet back then. Rather the Funny Car racers would simply obtain street Hemi cylinder heads, port them, cut a valve job and use then until they were cracked or broken. It wasn’t uncommon after an event to walk through the pits and see a dozen cast iron cylinder heads laying around.

The last Hemi parts built by Chrysler was in 1971 so as Maskin tells the story, “I called Tom Hoover, who is the father of the 426 Hemi, and I asked if he had any aluminum head tooling that he wasn’t using anymore. Hoover hooked me up with Brian Schram at Direct Connection who said they had some tooling that I was welcome to come and have with only one condition. He asked that ‘if’ I get these to work, could they buy the heads back from me?’ That was a no-brainer. You’re going to give me this stuff and pay me to buy them back?”

Maskin quickly picked up everything they had, eventually producing Dart’s first cylinder head, a cast aluminum Hemi head for the fuel teams of the day.

“We worked day and night and in three or four weeks’ time, we had a set of cylinder heads ready to go on Billy Meyer’s car during a match race,” Maskin said. “They had never run aluminum heads before and I told him to richen the engine up. What I don’t think they understood at the time was that when you fix the exhaust port as we did, you’re evacuating more of the cylinder charge so you have to richen the engine up. Well, lo and behold, he sets the track record by a tenth of a second!”

By the end of 1981, Maskin sat at the last race of the year with a pad and pen taking orders for his heads from just about every major team of the day.

At that point in history, Maskin teamed up with St. Denis purchasing their first machining center together with a loan from St. Denis’ father. Eventually the partnership, along with others fizzled but the Dart name and its reputation continued on. Maskin teamed with Dave Tratechaud who had his own machine shop and did some work for Maskin. The two are still at it today with possibly the largest machining facility of its type in North America. Thirty six machining centers occupy the Dart facilities in Troy, Melvindale and Richmond, Michigan.

“From 1981 to 1991,” Maskin says, “I built what I knew how to build based on what I had learned prior to ’81.”

In 1988, Maskin teamed up to start World Products, a venture he is no longer involved with, but it all came about through his ability to produce cast iron cylinder heads with quality and accuracy.

In the early ‘90s, with the feeling of some unfinished business, Maskin reentered the world of Pro Stock racing with Mark Pawuk. The same 500-inch engines utilizing his own ideas for horsepower powered Jim Yates and Jeg Coughlin to a combined three world championships and countless national event wins.

“When I got back into racing,” he says, “I had all the resources I needed that I didn’t have my first time around. I had a company, money and I never felt as if I finished the job I had started in the ‘70s. I learned quite a bit more but it was all based on what I knew.”

In addition to Dart’s standard fare of cast iron and aluminum small and big block Chevrolets, Fords, LS blocks and full line of performance heads, Dart is also producing custom water jacketed billet blocks and heads machined from a solid hand forged ingot giving the racer the ability to turn their dream into a reality. Dart’s quality engineering, machining capability and years of experience have helped top engine builders create special one-off projects from in-line four and six cylinder designs to super tall deck raised cam small block Fords and they certainly don’t stop there. This impressive manufacturing capability and product diversity has led to countless NHRA Top Fuel, Funny Car and nitrous injected Pro-Modified victories, and as Maskin says, “It’s all derived from the technology we’ve gained over the years.”

PHOTO GALLERY

Invalid Displayed Gallery

(Click to enlarge)

SOURCE:

Dart Machinery

353 Oliver St.

Troy, MI 48084

248-362-1188

www.dartheads.com

This story was originally published on January 19, 2015.