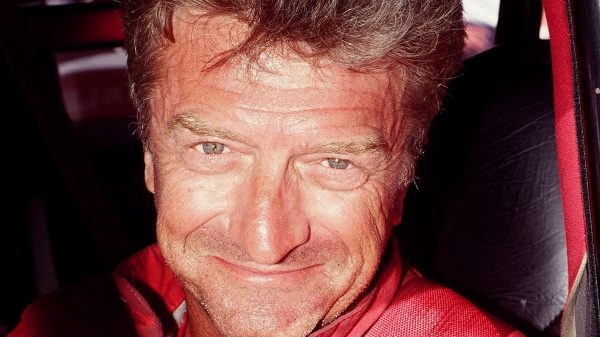

Standing in front a steel workbench inside the blue-tin-lined walls of his Jefferson City transmission shop, Missouri’s Mark Micke is meticulously inspecting center support clearances inside the aluminum case of a Turbo-Hydramatic 400 he’d started assembling early this morning. Clean-shaven and sporting a fresh-out-of-the-plastic black tee emblazoned with his business’ logo tucked into a pair of dark blue jeans, he does all he can to hide it, but his eyes tell the story. He’s tired.

The newly crowned NMCA Super Street Outlaw and ADRL Pro Drag Radial champion is every bit as proud of his latest accomplishments as he should be, but the quest that started over eight months ago and has included 18 races, a self-described “shitload” of testing and the associated red-eye flights and all-night drives has clearly taken its toll. It’s the never-ending conundrum of having too much to do and too little time to do it, yet Micke, 46, wouldn’t have it any other way. It’s hard work that has consistently produced results for him—in life and on the race track—and those results and forward progress have only fueled the desire for more. It’s the essence of his mind and spirit, and, arguably, his prowess as a racer.

“So, two different championships, two different classes, two different organizations,” I begin, hoping for a deep, retrospective take on what by any driver’s standards would be a career year.

“Pretty bad ass,” Micke responds.

“At the bare minimum,” I say, pun intended.

Micke steps over to his hugger orange Super Sport Camaro commemorative edition Snap-On toolbox, grabs a custom-built billet valve body out of a box in the top and heads back to the work bench. He’s not taking the bait. More racers than not are humble almost to a fault—hesitant to boast or unintentionally come off cocky while expounding on their success—but there has to be something that will get him up on the tire. With business handled in both NMCA and ADRL competition and those series’ schedules complete, Micke and Jason Carter, the owner of the blue 1978 Chevy Malibu they’ve campaigned together in 2013, have one last outing slated before parking their program for the year: a big money, no-holds-barred drag radial race at Mississippi’s notoriously fast Holly Springs Motorsports Park.

Micke steps over to his hugger orange Super Sport Camaro commemorative edition Snap-On toolbox, grabs a custom-built billet valve body out of a box in the top and heads back to the work bench. He’s not taking the bait. More racers than not are humble almost to a fault—hesitant to boast or unintentionally come off cocky while expounding on their success—but there has to be something that will get him up on the tire. With business handled in both NMCA and ADRL competition and those series’ schedules complete, Micke and Jason Carter, the owner of the blue 1978 Chevy Malibu they’ve campaigned together in 2013, have one last outing slated before parking their program for the year: a big money, no-holds-barred drag radial race at Mississippi’s notoriously fast Holly Springs Motorsports Park.

I try a different tack: “I’m curious…what’s stopping you from calling it a day and putting a bow on one hell of a race season? What’s left to prove?”

“Everything.”

It’s perfect. It’s more than perfect. It’s powerful, pointed, uncanny. And it says more of Micke than any longwinded, wide-ranging reflection ever could, near perfectly surmising his passion for progress, be it forward, backward or sideways. Look no further than the years of trial and error he experienced alongside his brother, Ryan, working to turn an experimental centrifugal supercharger engine program into a staple of Outlaw 10.5 and Pro Mod-style drag racing. Micke’s racing career has been rooted in taking action, trying things and taking chances based entirely on his faith in his own abilities, and the belief that doing what others either can’t or won’t will ultimately separate him from the competition.

The only problem is that his answers are getting shorter, and they weren’t of great length to begin with. Micke doesn’t volunteer any further explanation. Later on, when I press him, he’ll say that winning two championships in one year was “something he takes a lot of pride in,” especially considering his ADRL title was the first-ever awarded to the organization’s newest eliminator, Pro Drag Radial, and that his second NMCA crown made him the only driver ever to win titles in both Pro Street and Super Street, the street-legal sanction’s two premier categories.

Still, though, he’d rather stick to matters not yet resolved. “Let me put it this way,” he says, responding to my  continued badgering about his having little room to improve on the last few months of his life, “what I’m looking at, and what all these other guys are looking at, is that this deal at Holly Springs is one of those badass races. Nobody is going down there worried about winning money or a trophy; you go down there to make a statement, to be the guy everyone talks about all winter. Between the track, the conditions, the fact that it’s a run-what-you-brung deal on radial tires and all the heavy hitters will be there; it’s the kind of race that lets you know where you stand.”

continued badgering about his having little room to improve on the last few months of his life, “what I’m looking at, and what all these other guys are looking at, is that this deal at Holly Springs is one of those badass races. Nobody is going down there worried about winning money or a trophy; you go down there to make a statement, to be the guy everyone talks about all winter. Between the track, the conditions, the fact that it’s a run-what-you-brung deal on radial tires and all the heavy hitters will be there; it’s the kind of race that lets you know where you stand.”

For Micke, who seems to be glossing over the fact that no matter what happens between now and next year he’ll still be ordering a set of vinyl number-one decals for the windows of his G-bodied doorslammer, there will soon be a piece of paper—a final qualifying sheet—with a number next to his name that he’ll use to evaluate his season. And there will be no reflection until the smoke clears in Mississippi.

“Everyone is going after the big number; there’s a couple of possibilities; someone going in the teens and someone going 200 miles per hour—but that’s never really been something I’ve gotten caught up in,” he tells me, his manner seemingly speaking to some unscratched itch, a need to stray from his usual race-day strategy as he explains how he’s consciously avoided the swing-for-the-fences approach a lot of racers thrive on. “We’ve always raced for championships,” he says. “You might lose a battle, but you’re going to win the war type of thing; that’s what we were going after all year. In outlaw racing, that’s not a mindset everyone has. Most guys are going for the big number, and I want the big numbers, too, but you set a record today and next week somebody else resets it; everybody forgets who you are. But if you got championships, nobody can take them away from you.”

It’s easy to make sense of such logic, but it’s equally easy to see the other side of the argument. Champions are certainly made in the regular season and playoffs, but there’s no denying that more than one legend has been born on all-star weekend during a homerun derby. Micke—who’s been involved in drag racing long enough to know that this sport has always celebrated its long-ball hitters, be it Kenny Bernstein, Jason Scruggs or Tim Lynch—recognizes the opportunity to be a part of history, and it’s impossible for him to ignore it. Before day’s end, I’ll watch as Micke avoids virtually every opportunity to bask in the glory of his past accomplishments or exhibit any amount of contentment. But that’s not to say he’s not happy—more like thrilled—to be doing what he’s doing. Through the course of a 12-hour work day it would be impossible to count how many times he’d say, “I love this shit,” when talking about drag racing. And it’s absolutely true, evidenced by virtually every aspect of his life—family, friends and business—all revolving around the same tire-smoking sun. Mark Micke simply has a fundamental fear of complacency.

It’s easy to make sense of such logic, but it’s equally easy to see the other side of the argument. Champions are certainly made in the regular season and playoffs, but there’s no denying that more than one legend has been born on all-star weekend during a homerun derby. Micke—who’s been involved in drag racing long enough to know that this sport has always celebrated its long-ball hitters, be it Kenny Bernstein, Jason Scruggs or Tim Lynch—recognizes the opportunity to be a part of history, and it’s impossible for him to ignore it. Before day’s end, I’ll watch as Micke avoids virtually every opportunity to bask in the glory of his past accomplishments or exhibit any amount of contentment. But that’s not to say he’s not happy—more like thrilled—to be doing what he’s doing. Through the course of a 12-hour work day it would be impossible to count how many times he’d say, “I love this shit,” when talking about drag racing. And it’s absolutely true, evidenced by virtually every aspect of his life—family, friends and business—all revolving around the same tire-smoking sun. Mark Micke simply has a fundamental fear of complacency.

“When I started out I never thought about what might happen or what we might do,” he says, buttoning up an Australian customer’s TH400 unit that’s destined to ship today. “I don’t even think about it now. You fall into stuff; you work hard and stuff works out. I’ve been lucky to align myself with good people over the years and be a part of some outstanding teams. Personally, I don’t want to be the guy that just exists or whatever, lives on what they did last week or last year. Whether it’s good or bad, I want to feel like we’re always trying to improve.”

The Tao of Micke is admittedly old school, but its principles have stood the test of time and, more importantly, always get results. Micke arrived at his current posts—multi-time world champion, successful businessman, husband and father (he regularly interjects into any racing-related conversation how thankful he is that his wife, Maria, and daughters, Lauren and Brooke, put up with his “obsession”)—through his lifelong subscription to the theory that no one cares about your race car, transmission shop or family the way you do.

“Racing wise, I think one of the biggest advantages is being able to do it yourself,” he says. “We’ve always done almost everything ourselves; we’ve never had to rely on other people to come do it for us; other than like paint work or chassis stuff. If we need to make parts for the car, we make them. We do our transmissions, converters, tune-ups and whatever else we need to do. We do it all.”

Being able to do the physical, mechanical work involved with racing is one thing, but being able to leverage that ability to successfully navigate the elimination rounds of a high-level heads up race is not a foregone conclusion. “I mean, I would say that I feel given an equal playing field, we can outrace 95-percent of the guys out there that we race against,” Micke finally admits. “I think I understand, and as a team, too, we understand what the race car does out on the track. Maybe some of it comes natural to us, but, speaking for myself, I feel confident that on any given weekend I can look at what I want to do with the car or what we need it to do, look at the numbers, the track, the weather and the computer, and pretty well make the car do it.”

In a time when hired crew chiefs and tuning consultants are the norm and a front-running engine program, race car or turnkey operation is only a wire transfer away, Micke feels good in knowing that things like God-given ability, experience, ingenuity and work ethic can and will make all the difference—especially in a sport where winning and losing is dictated by hundredths- and thousandths-of-a-second. “Money is always going to play a role, especially in heads-up racing, but it’s not all money,” he insists. “You pretty much have to have good stuff, but you’ve got to be able to do something with whatever you have, and I think that’s where we’ve got a leg up anywhere we go.”

Micke’s aversion to ballyhooing yesterday’s medals and penchant for the here-and-now make him hard to interview  in any conventional, structured fashion, but they also make him an absolute joy to bullshit with. He exudes a unique rock-and-roll swagger by talking not about what he’s already done, but what he’s going to do. He also has the kind of analytical mind and experimental tendencies that keep his wheels spinning 24 hours a day, seven days a week—working in the racing industry only further compounds matters. “It’s a blessing and a curse,” he says. “There are a lot of old guys that will tell you to be careful not to make your hobby your job, but that’s exactly what I’ve done. You wake up one day and realize that you’re totally consumed with this; totally consumed. And I’ve been fortunate that my family, my wife, have just grown to deal with it, but they understand that now, at this point with our business, it’s how we put food on the table.”

in any conventional, structured fashion, but they also make him an absolute joy to bullshit with. He exudes a unique rock-and-roll swagger by talking not about what he’s already done, but what he’s going to do. He also has the kind of analytical mind and experimental tendencies that keep his wheels spinning 24 hours a day, seven days a week—working in the racing industry only further compounds matters. “It’s a blessing and a curse,” he says. “There are a lot of old guys that will tell you to be careful not to make your hobby your job, but that’s exactly what I’ve done. You wake up one day and realize that you’re totally consumed with this; totally consumed. And I’ve been fortunate that my family, my wife, have just grown to deal with it, but they understand that now, at this point with our business, it’s how we put food on the table.”

Does he think there’s any other way to succeed in a sport that chews people up and spits them out as quickly as drag racing? To put it simply; no way, it’s one of those “all-or-none deals” he explains, adding that desire is “probably the one thing” that money or a big budget can’t buy. “For guys like me, and there’s several; guys like Kyle Huettel, Kenny Hubbard, Mark Woodruff, just go down the list; we all have the sickness so bad that we’ll do whatever it takes. If it means we’ve got to work all day every day, then we’re going to work all day every day. And, to tell you the truth, there’s no way to hold us back because there’s no rules against it; no rules against how much work you put into it.”

He has surprising views on outlaw racing, particularly for someone who spent several years crisscrossing the southeast chasing big money in the virtually lawless world of 10.5-tire racing. Micke admits that while the no-rules nature is what makes that style of racing so exciting and appealing to guys like himself, it’s also “exactly what sends these classes spiraling out of control” both in terms of the performance and dollars required to compete. Throughout  the early 2000s, for Micke, along with his aforementioned brother, Ryan, and crew chief Jeff Dickey, the Outlaw 10.5 scene served as the proving grounds for the team as they experimented with a series of high-horsepower superchargers being produced by Kansas-based ATI ProCharger. Working hand-in-hand with the company in the research and development of their massive 3,000-horsepower-plus capable F3 and F4 blowers, Micke and company made their name in the small-tire racing circles, but the writing was on the wall. “That Outlaw 10.5 thing just took off,” he says, emphatically. “It was something nobody had ever seen and everybody fell in love with it. And it was so competitive that it just went crazy, but the problem was that a lot of guys doing it—like myself—were all budget-oriented people; we’re working for a living. The more competitive it got, the more money it took to hang, and within a couple years it was just out of control and it started dying. A lot of guys started figuring it out, like I did, saying, ‘Oh shit, I’m in over my head a little bit’ and started to pull back. It was an insane time—an awesome time—but it was a freight train off the tracks. I don’t think it could sustain itself.”

the early 2000s, for Micke, along with his aforementioned brother, Ryan, and crew chief Jeff Dickey, the Outlaw 10.5 scene served as the proving grounds for the team as they experimented with a series of high-horsepower superchargers being produced by Kansas-based ATI ProCharger. Working hand-in-hand with the company in the research and development of their massive 3,000-horsepower-plus capable F3 and F4 blowers, Micke and company made their name in the small-tire racing circles, but the writing was on the wall. “That Outlaw 10.5 thing just took off,” he says, emphatically. “It was something nobody had ever seen and everybody fell in love with it. And it was so competitive that it just went crazy, but the problem was that a lot of guys doing it—like myself—were all budget-oriented people; we’re working for a living. The more competitive it got, the more money it took to hang, and within a couple years it was just out of control and it started dying. A lot of guys started figuring it out, like I did, saying, ‘Oh shit, I’m in over my head a little bit’ and started to pull back. It was an insane time—an awesome time—but it was a freight train off the tracks. I don’t think it could sustain itself.”

By the time I’m finally able to convince Micke to close up shop for the day, the late summer sun is fading into the horizon. This particular Midwest evening is colder than either of us is used to, but it’s one of the few times when having to dig a jacket out from behind the seat feels like a positive development. “Man, if the weather stays like this,” he says, eyes wide, “Holly Springs is going to be a blood bath.”

The plan this season was relatively straightforward for Micke, who had actually stepped away from fielding his own race car in recent years, electing to focus on family and business instead. Having teamed up with longtime friend and customer, Jason Carter (“He suckered me in,” he says, jokingly), it was decided that chasing points in NMCA Super Street Outlaw—familiar territory for them both—made the most sense. The muscle car-based series with its six-race schedule is regional enough, and the events are of the necessary scale to well serve their newly signed sponsor Garrett by Honeywell, the massive turbocharger technology conglomerate.

But a simple and concise schedule was not to be. “I was still helping some guys and, of course, building transmissions for a lot of ‘em, but I’d basically gotten out of actually racing,” says Micke. “Jason was running his Malibu, though, and he’d had me come to the track a few times to help here and there. We were having a good time and making progress with the car to the point where the racer in me—in both of us—just kind of took over. We knew that together we could contend for a championship in NMCA, and that’s the kind of thing that your sponsor wants to see; it shows you’re dedicated, that you can see something through. But right from the start of the year, all the chatter was about Outlaw Drag Radial and then news breaks that the ADRL is going to start a Pro Drag Radial class. It just takes over; you see a place to race where you think you can win and the next thing you know you’re loading up the trailer.”

Micke doesn’t hesitate to call it a sickness, the inability to resist the siren’s call that is drag racing. “I’ve never been a drug addict but it can’t be any worse than this shit,” he says. “It’s a bitch. You get caught up in it; the competition, that drive to outrun the next guy, be the best; it’s crazy. And then you try to step back, but you blink your eyes and you’re right back in it. It’ll consume everything; all your time, all your money, all you have to give it.”

Part of the problem, strangely, has been that Mark Micke is pretty damn good at all this. Walking away from drag racing or tempering one’s involvement borders on impossible for even the also-rans and perennial non-qualifiers of the world, so it’s not hard to imagine the challenge walking away would be for someone who has every reason to believe he’s got a shot at winning anywhere he goes. The mental and emotional baggage that is self-imposed high expectations, however, can be as hard to manage as a 55-gallon drum carry-on. Identifying why you’re doing what you’re doing can become increasingly difficult in the thick fog produced by drag racing’s adage that you’re only as good as your last pass. So much so, Micke believes, that it’s “easy to get caught up and lose sight of the big picture”, which has to be simply doing something you enjoy.

Part of the problem, strangely, has been that Mark Micke is pretty damn good at all this. Walking away from drag racing or tempering one’s involvement borders on impossible for even the also-rans and perennial non-qualifiers of the world, so it’s not hard to imagine the challenge walking away would be for someone who has every reason to believe he’s got a shot at winning anywhere he goes. The mental and emotional baggage that is self-imposed high expectations, however, can be as hard to manage as a 55-gallon drum carry-on. Identifying why you’re doing what you’re doing can become increasingly difficult in the thick fog produced by drag racing’s adage that you’re only as good as your last pass. So much so, Micke believes, that it’s “easy to get caught up and lose sight of the big picture”, which has to be simply doing something you enjoy.

“I think racing with Jason, I’ve been better,” he says. “One thing I can say, this year we’ve had a blast. Me and Jason, Chad [Simpson] and Frank [Durham], we’re having a good time and just enjoying all this. At some point over the years, I got caught up in it and it wasn’t fun anymore.”

As we drive toward a local bar and grill for a quick bite to eat, Micke explains that no matter how you slice it, realistically speaking, you’re going to lose a lot more than you win when you go drag racing. “It’s important to learn how to do it,” he says. “I don’t care who you are, you’ve got to learn how to do it.” His emphasis on the subject illustrates the extent to which he believes what he’s saying—and Micke’s reasoning is sound. “The difference between winners and losers is that winners learn from losing, and losers don’t,” he continues, beginning to wax philosophically. “Losing makes you appreciate winning and respect how much work and preparation went into it. Losing makes you learn how to control your emotions and examine what you’re doing.”

Don’t let him fool you, though. Losing may be part of the deal, but it’s not Micke’s favorite. “Oh, I hate to lose,” he says. “I’m not a bad loser by any means, but I hate it; I hate to get outrun and I’ll do whatever it takes to prevent it.”

Over the quintessential middle-American meal of choice, steak and potatoes, Micke’s illness, which likely could be clinically diagnosed, is never more apparent. He’s dissecting the big blue Malibu’s 60-foot to 330 numbers, pointing out that it’s the first few hundred feet of the track that separates the top teams in Outlaw Drag Radial. “Let’s be serious, you take a turbo car with 3,500 horsepower and from 200-foot on it’s going to haul ass. You can’t hardly screw it up,” he admits. “Going fast down low; that’s the difference maker, and the competition has us all pushing each other.”

Trying to race, win and go fast with extremely limited traction, such as is the case in Drag Radial or 10.5-tire racing, has always been most attractive to strategists; those interested as much or more in the challenge of tuning the car as the thrill of driving it. Although accomplished behind the wheel, it’s painstakingly obvious that Micke gets a good bit of his kicks behind the computer screen. “These drag radials will make you pull your hair out,” he says. “You can make a hit, you can go 4.25—not touch the car, track stays the same, weather stays the same—and the next time the car blows the tires off, doesn’t even move.” Compared to his days in Pro Street racing with a massive set of 34-inch-tall, 17-inch-wide slicks—yet, comically, essentially the same amount of horsepower—it’s a tremendous change of pace. “Over there you’re chasing wheel speed, needing to get the car to spin the tire; and over here, with these radials, you can’t let it spin. It has to be dead hooked from the moment you leave. If it spins, it’s over with; it won’t come back.”

From torque converters and ignition timing to boost levels and shock settings, the variables that Micke is talking about, speaking only of the race car, would send a scientist into a psychotic break, but there’s nothing in his voice that would suggest anything other than absolute exhilaration. Like a teenager trying to beat the next level of a video game or get a higher score, studying strategy guides and hoping to find a cheat code, Micke is every bit as eaten up with this stuff as he claims he is, and the intensity level rarely waivers.

“One thing I try to do and I think I’m good at is watching and learning,” he says, continuing our dinner’s dedication to the importance of data in racing. “If I watch fast cars, I try to figure out what they’re doing, and I try to translate that to our program. Not everyone is big on watching other people make passes, but I’m convinced you can learn a lot from it.”

Pausing briefly, perhaps realizing we’re both done with our meals and have spent an entire day together yet literally never spoke about anything other than drag racing, Micke continues, surely realizing there’s no point in trying to diversify the conversation now. “It’s ridiculous. I know it is. Years ago, it was a totally different game, but now,” his voice trails off as he smiles slyly and shakes his head, “it’s nuts.”

If, by chance, Micke hasn’t yet gotten it all figured out, it’s certainly not for lack of effort. Since his first trip to the Street Machine Nationals at South Missouri’s Ozark International Raceway—the race that set the hook for his obsession—he’s been a student of the game. Admittedly, a lot has changed since those early days, but there’s quite a bit that hasn’t. “Back in the beginning, we weren’t very professional,” he says. “We were just doing it because we loved to do it.” Again, he takes a second to collect himself before saying what we’re both thinking. “Well, I guess that’s still why we’re doing it.”

Morning to night—at work, at dinner, at home—the story remains the same. And that’s what Micke believes it takes. With him there’s no halfway, no middle ground, and literally, nothing else to talk about. “There’s not much difference between hero and zero right now,” he says. “And I’m not about to let someone working harder than me be the deciding factor. I haven’t yet, and I don’t see any reason to start now.”

Me either.

This story originally appeared as the cover story in Drag Illustrated Issue No. 80 in August/September of 2013.

Photographs by Ian Tocher, Kyle Kramer and Mike Galemi

This story was originally published on September 29, 2016.